✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🧠 Sound smart? Feed your brain with weekly issues sent directly to your inbox here

Today’s Bullets:

- The Agencies

- The Ratings Scale

- Credit Spreads and Implications

- Tripping Covenants & Default

- Sovereign Nightmare and Bitcoin

Inspirational Tweet:

“The weakness is broadening out. It tells you that at the margin, this is not just a rates issue, it’s also a credit issue. There are not many companies that can finance at north of 10 per cent for a sustained period of time.”https://t.co/a1qOs3oQUK

— Michael Pettis (@michaelxpettis) May 4, 2022

Michael is pointing out here that as bond yields rise, particularly for stressed (high yield) and distressed companies, many will be unable to continue to finance their operations for long. So, as yield spreads widen, corporate failures multiply.

If that sounds confusing to you, no worries. We’re going to break all down right here.

🏛 The Agencies

First, just like consumers have credit agencies watching over them and rating their credit-worthiness, so do companies and countries (sovereign bond issuers). Also like consumers, bond issuers have three main agencies judging them. And finally, just as the consumer credit agencies sometimes struggle to make accurate analyses, so do the bond rating agencies.

Shocking, I know.

Still, both sets of agencies can have major impacts on the abilities of people, companies, and even countries to borrow money and finance their purchases or activities. And this, in turn, can have profound impacts on their businesses or currencies and ability to be a going concern, i.e., a healthy operation.

So who are the agencies?

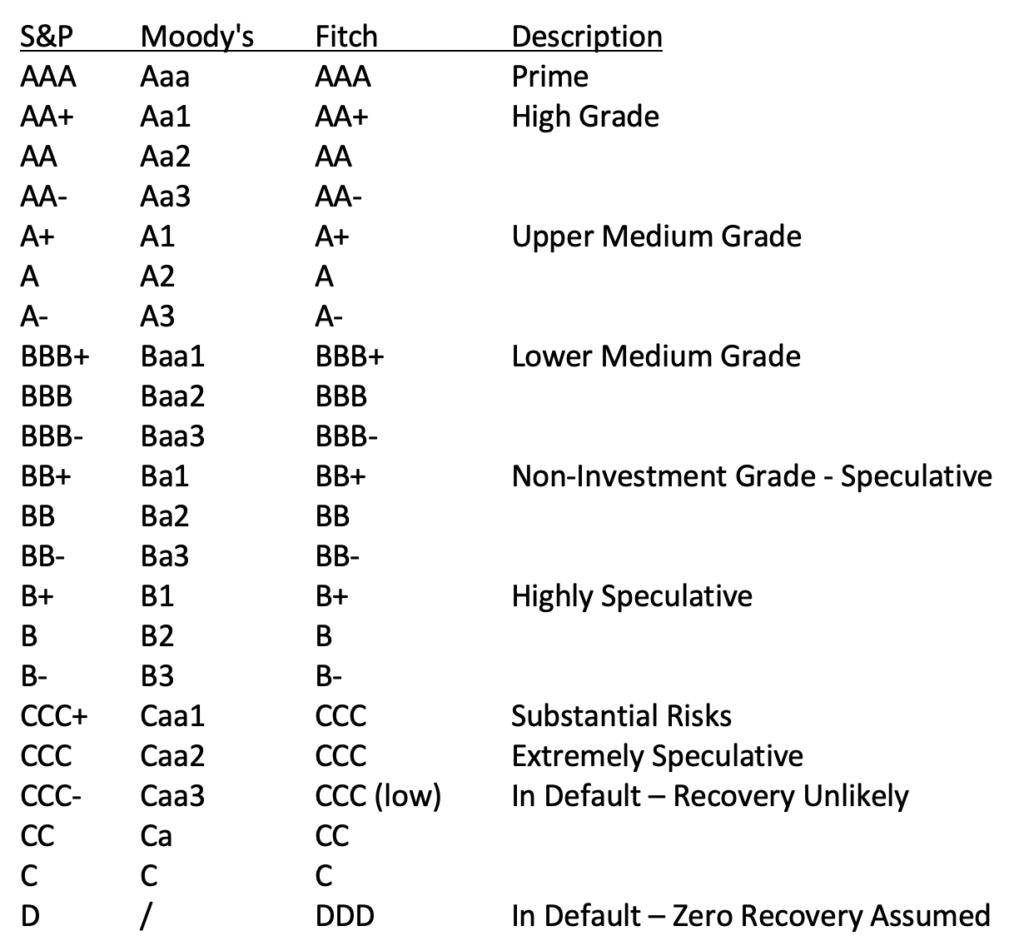

Well, here in the US, we have Standard and Poor’s (yes, the S&P 500 Index creator), Moody’s, and Fitch. They have their own little nuances in ratings (see chart in the next section), but stay in lock-step with each other for the most part, as far as the grading is concerned.

Let’s break down the ratings scale and significance of the grades.

⚖️ The Ratings Scale

On the face of it, consumer credit ratings and bond credit ratings work quite similarly. The higher the grade, the more credit-worthy the borrower is deemed. As you may know, the consumer scale is between 300 and 850, and a Prime borrower will have a score above 800. Anything below 620 is considered Sub-Prime, and these borrowers find it more difficult to get credit for purchases, say for a house or car or to open a new credit card or line of credit. Under 580, and you are considered in personal default and it’s almost impossible to get a loan or credit with a score this low.

For corporations or countries, the similar is true. A score of AAA means you are a Prime borrower and deemed to be the ultimate low risk to lenders. This score is generally reserved for the strongest countries and a handful of companies at most. Today, only a few companies wear the AAA badge: Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft, Northwestern Mutual Insurance, and New York Life Insurance.

As for countries, there are also only a handful of AAA rated sovereigns, including Germany, Australia, and a number of Nordic European countries. But what about the USA?

Well, currently the US is close, but not quite AAA across the board, as S&P lowered their rating to AA+ and Fitch has issued a negative outlook on their AAA rating, meaning they will likely downgrade the US to High Grade in the next report.

Your next question may be, what’s the equivalent of sub-prime for the bond credit scale? This is where it gets a bit more intricate. When a sovereign or company falls below BBB-, that’s when they are no longer considered Investment Grade and are deemed a speculative investment by the ratings agencies and considered junk grade to investors.

See below:

What’s so important about this is that when a borrower falls below Investment Grade in the bond world, they are immediately precluded from investment by many institutional investors, as those investors’ fund mandates will not allow it. This means that the junk-rated company must offer a higher interest rate or coupon on their debt to attract investments from alternative sources. This higher coupon means a higher cost to borrow, and a higher cost to borrow means a higher cost of operating their business (or government). This in turn raises the risks of their ability to remain a going concern even more than when they were just a notch higher on the ratings scale.

The vicious downgrade cycle begins.

🤏 Credit Spreads and Implications

Back to the Tweet above by Michael. When looking at a broad section or even the entire market, we sometimes see a shift in interest rates on a whole bunch of corporate bonds versus the Fed Funds or the risk-free interest rate. This gap is called the credit spread and when credit spreads widen for a growing section of the corporate market, this can have implications for the entire bond market. See, as credit spreads broaden to numerous sectors or credit grades (i.e., BB and below), this means that many companies must pay more for their borrowing, and this generally means we will see a slowdown in the economy as a whole.

As the economy slows and contracts, we often see a number of high-yield rated companies (BB+ and below) slip in earnings and eventually either trip a covenant or default on a payment of their bonds.

But wait, what the heck does tripping a covenant mean?

🤕 Tripping Covenants & Default

Think of tripping a covenant like a trigger on an agreement, a threshold you have to stay above to remain in good standing with the lender. For instance, let’s say that the bank that extended you a loan for your car stipulated that your earnings had to stay above a certain level for you to remain a good borrower, continue with the loan, and keep the car.

Then, if your earnings fell below that level for a month or two (depending on the agreement), the bank could claim that you tripped the covenant (agreement) and they could pull your loan, and seize your car.

But wait, you didn’t miss a payment or anything, you just had a bad month at work! You’re still making payments!

Exactly. Tough luck, kid.

And so, when a company trips a covenant, which can apply to many types of financial measures, but in this instance, it means that their revenue or earnings dipped below a certain level and this made their debt to revenue or earnings ratio hit a level that is outside of the agreement. The company is said to have tripped a covenant, and the lender can pull the line of credit or loan. When this happens, the lender will typically work to renegotiate the terms (highly in their own favor) to come to what we call a remedy or cure for the covenant infraction. Higher interest rates, accelerated payment schedule, penalty payments, or other sometimes draconian measures.

So why does this all matter?

Well, as you can imagine, as the economy contracts, credit ratings fall, borrowing rates rise, earnings fall, and numerous companies find themselves in the position of having to renegotiate terms on prior agreements just to continue operating. It becomes a cascade of negative events that can lead to much higher interest payments coupled with lower earnings, and eventually the company missing a payment.

And as we noted above, when a company misses a payment, they are said to be in default. When this happens, they are immediately downgraded to distressed status. They are relegated to the bottom of the ratings scale and considered the highest risk investment in the bond world.

But this is just a company. What happens if a country misses interest payments? What if a country defaults?

😱 Sovereign Nightmare and Bitcoin

When a country misses a payment on its debt and it isn’t due to a simple vote to expand the budget or other political nonsense, but has deeper financial health implications, a series of devastating events can occur.

First, anyone who holds the bonds of that country will most likely seek to liquidate them, causing the prices of the bonds to fall and the rates to rise. When investors sell the bonds, they will receive the country’s currency in return. The investors will then sell that currency for their own country’s currency, causing the distressed country’s currency to fall. As more and more investors do this, a cascading event occurs and the currency eventually collapses.

This event is better known as hyperinflation.

But what if you’re a resident of that country? All of your money and real estate or investments are denominated in that country’s currency? What can you do to protect against this?

First, be on the lookout for your country’s credit rating and whether it begins to slip below A-status or worse. A website I sometimes use to monitor sovereign bond ratings is here.

Also watch the Credit Default Swap (CDS) market and where your country’s CDS is trading. If you have no idea what that means, don’t stress, I already wrote all about that in a previous Informationist Issue. You can find it here.

Then, the most important step to take is to protect your money, get your savings out of your base currency and into a store of value (SoV) such as physical gold and Bitcoin. Note, Bitcoin may be the only way to secure and transport your savings if your country’s currency and social fabric both disintegrate rapidly, like we’ve recently seen in Ukraine.

Additionally, there is always a chance we begin to see a total collapse of the fiat system across the globe. You may have heard me talk about it before, but this is why I believe one of the most important holdings in your portfolio can be Bitcoin. And unless your country is beginning to experience hyperinflation, a huge allocation is not necessary. A 1% to 5% allocation can not just help you, but it may be able to protect your entire life’s savings from being destroyed.

If you are wondering how, I wrote all about it in a thread recently on Twitter. And if you’ve already read it, great. If you haven’t read it yet or you’d just like a refresher, you can find it right here:

As a risk trader, I’m always concerned about 'Tail Risks'.

And #Bitcoin hedges against the biggest tail risk we’ve ever faced in the history of the modern financial world:

An all out collapse of fiat currencies.

How? Let’s break it down nice and easy here 👇🧵

— James Lavish (@jameslavish) February 15, 2022

That’s it. I hope you feel a little bit smarter knowing about credit ratings, spreads and defaults, and know what signs of distress to look out for in your own jurisdiction, be it the US or elsewhere, and how to protect yourself.

As always, feel free to respond to this newsletter with questions or future topics of interest!

✌️Talk soon,

James