A Firefighter’s Take On Today’s Precarious Economic Mechanics And How Bitcoin Steps In As An Empowerment Tool For The Middle Class

By Dan — Co-Host of Blue Collar Bitcoin Podcast

A Preliminary Note To The Reader: Much of this piece assumes the reader possesses a basic understanding of Bitcoin and macroeconomics. For those who don’t, items are linked to corresponding definitions/resources. An attempt is made throughout to bring ideas back to the surface — if a section isn’t clicking, keep reading to arrive at summative statements. Lastly, The focus is on the U.S. economic predicament; however, many of the themes included here still apply internationally.

CONTENTS

PART 1: Fiat Plumbing

- Introduction

- Busted Pipes

- The Reserve Currency Complication

- The Cantillon Conundrum

PART 2: The Purchasing Power Preserver

PART 3: Monetary Decomplexification

- The Financial Simplifier

- The Debt Disincentivizer

- A “Crypto” Caution

- Conclusion

PART 1: Fiat Plumbing

Introduction

When Bitcoin is brought up at the firehouse, it’s often met with cursory laughs, looks of confusion, or blank stares of disinterest. Despite tremendous volatility, Bitcoin is the best performing asset of the last decade, yet most of society still considers it trivial and transient. These inclinations are insidiously ironic, particularly for members of the middle class. In my view, Bitcoin is the very tool average wage earners need most to stay afloat amidst an economic environment that is particularly inhospitable to their demographic.

In today’s world of fiat money, massive debt, and prevalent currency debasement, the hamster wheel is speeding up for the average individual. Salaries rise year-over-year, yet the typical wage earner often stands there dumbfounded, wondering why it feels harder to get ahead or even make ends meet. Most people, including the less financially literate, sense something is dysfunctional in the 21st century economy — stimulus money that magically appears in your checking account; talk of trillion dollar coins; stock portfolios reaching all time highs amidst a backdrop of global economic shutdown; housing prices up teens percent in a single year; meme stocks going parabolic; useless crypto tokens that balloon into the stratosphere and then implode; violent crashes and meteoric recoveries. Even if most can’t put a finger on exactly what the issue is, something doesn’t feel quite right.

The global economy is structurally broken, driven by a methodology that has resulted in dysfunctional debt levels and an unprecedented degree of systemic fragility. Something is going to snap, and there will be winners and losers. It’s my contention that the economic realities that confront us today, as well as those that may befall us in the future, are disproportionately harmful to the middle and lower classes. The world is in desperate need of sound money, and as unlikely as it may seem, a batch of concise, open-source code released to members of an obscure mailing list in 2009 has the potential to repair today’s increasingly wayward and inequitable economic mechanics. It’s my intention in this essay to explain why Bitcoin is one of the primary tools the middle class can wield to avoid current and forthcoming economic disrepair.

Busted Pipes

Our current monetary system is fundamentally flawed. This is not the fault of any particular person; rather, it’s the result of a decades-long series of defective incentives leading to a brittle system, stretched to its limits. In 1971 following the Nixon Shock and the suspension of dollar convertibility into gold, mankind embarked on a novel pseudo-capitalist experiment: centrally controlled fiat currencies with no sound peg or reliable reference point. A thorough exploration of monetary history is beyond the scope of this piece, but the important takeaway, and the opinion of the author, is that this transition has been a net negative to the working class.

Without a sound base layer metric of value, our global monetary system has become inherently and increasingly fragile. Fragility mandates intervention, and intervention has repeatedly demonstrated a propensity to exacerbate economic imbalance in the long run. Those who sit behind the levers of monetary power are frequently demonized — memes of Jerome Powell cranking a money printer and Janet Yellen with a clown nose are commonplace on social media. As amusing as such memes may be, they are oversimplifications that often indicate misunderstandings regarding how the plumbing of an economic machine built disproportionately on credit1 actually functions. I’m not saying these policy makers are saints, but it’s also unlikely they are malevolent morons. They are plausibly doing what they deem “best” for humanity given the unstable scaffolding they are perched on.

To zero in on one key example, let’s look at the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-2009. The U.S. Treasury Department and Federal Reserve are often maligned for bailing out banks and acquiring unprecedented amounts of assets during the GFC via programs like Troubled Asset Relief and monetary policies like quantitative easing (QE), but let’s put ourselves in their shoes for a moment. Few grasp what the short and mid-term implications would have been had the credit crunch cascaded further downhill. The powers in place did initially spectate the collapse of Bear Stearns and the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, two massive and integrally involved financial players. Lehman for example was the fourth largest investment bank in the U.S. with 25,000 employees and close to $700 billion in assets. But what if the collapse had continued, contagion had spread further, and dominoes the likes of Wells Fargo, CitiBank, Goldman Sachs or J.P. Morgan had subsequently imploded? “They would have learned their lesson” some say, and that’s true. But that “lesson” may have been accompanied by a huge percentage of citizen’s savings, investments, and retirement nest eggs wiped out; credit cards out of service; empty grocery stores; and I don’t feel it extreme to suggest potentially widespread societal breakdown and disorder.

Please don’t misunderstand me here. I am not a proponent of inordinate monetary and fiscal interventions — quite the contrary. In my view, the policies initiated during the Global Financial Crisis, as well as those carried out in the decade and a half to follow, have contributed significantly to the fragile and volatile economic conditions of today. When we contrast the events of 2007-2009 with the eventual economic fallouts of the future, hindsight may show us that biting the bullet during the GFC would have indeed been the best course of action. A strong case can be made that short-term pain would have led to long-term gain.

I highlight the example above to demonstrate why interventions occur, and why they will continue to occur within a debt-based fiat monetary system run by elected and appointed officials inextricably bound to short-term needs and incentives. Money is a base layer of human language — it is arguably mankind’s most important tool of cooperation. The monetary tools of the 21st century have worn down; they malfunction and require ceaseless maintenance. Central banks and treasuries bailing out financial institutions, managing interest rates, monetizing debt, and inserting liquidity when prudent are attempts to keep the world from potential devastation. Centrally controlled money tempts policymakers to paper over short-term problems and kick the can down the road. But as a result, economic systems are inhibited from self-correcting, and in turn, debt levels are encouraged to remain elevated and/or expand. With this in mind, it’s no wonder that indebtedness — both public and private — is at or near a species-level high and today’s financial system is as reliant on credit as any point in modern history. When debt levels are engorged, credit risk has the potential to cascade, and severe deleveraging events (depressions) loom large. As credit cascades and contagion enters overly indebted markets unabated, history shows us the world can get ugly. This is what policy makers are attempting to avoid. A manipulable fiat structure enables money, credit, and liquidity creation as a tactic to try and avoid uncomfortable economic unwinds, a capability I will seek to demonstrate is a net negative over time.

When a pipe bursts in a deteriorating home, does the owner have time to gut every wall and replace the whole system? Hell no. They call an emergency plumbing service to repair that section, stop the leak, and keep the water flowing. The plumbing of today’s increasingly fragile financial system mandates constant maintenance and repair. Why? Because it’s poorly constructed. A fiat monetary system built primarily on debt, with both the supply and price2 of money heavily influenced by elected and appointed officials, is a recipe for eventual disarray. This is what we are experiencing today, and it’s my assertion that this setup has grown increasingly inequitable. By way of analogy, if we characterize today’s economy as a “home” for market participants, this house is not equally hospitable to all residents. Some reside in newly remodeled master bedrooms on the 3rd floor, while others are left in the basement crawl space, vulnerable to ongoing leakage as a result of inadequate financial plumbing — this is where many members of the middle and lower classes reside. The current system places this demographic at a perpetual disadvantage, and these basement dwellers are taking on more and more water with each passing decade. To substantiate this claim, we’ll begin with the “what” and work our way to the “why.”

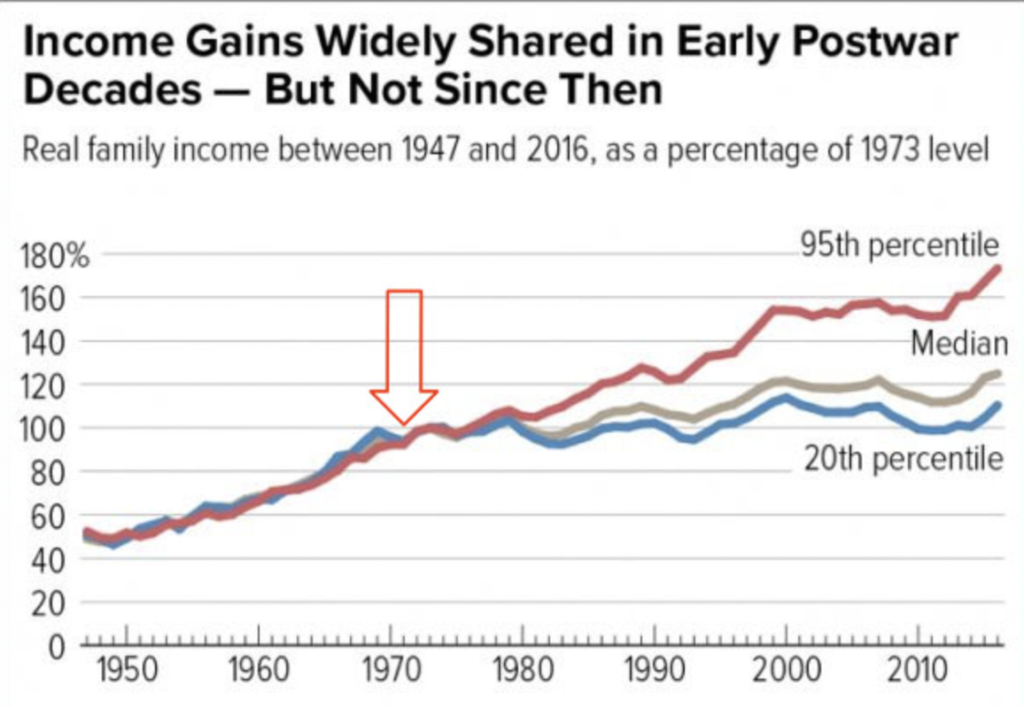

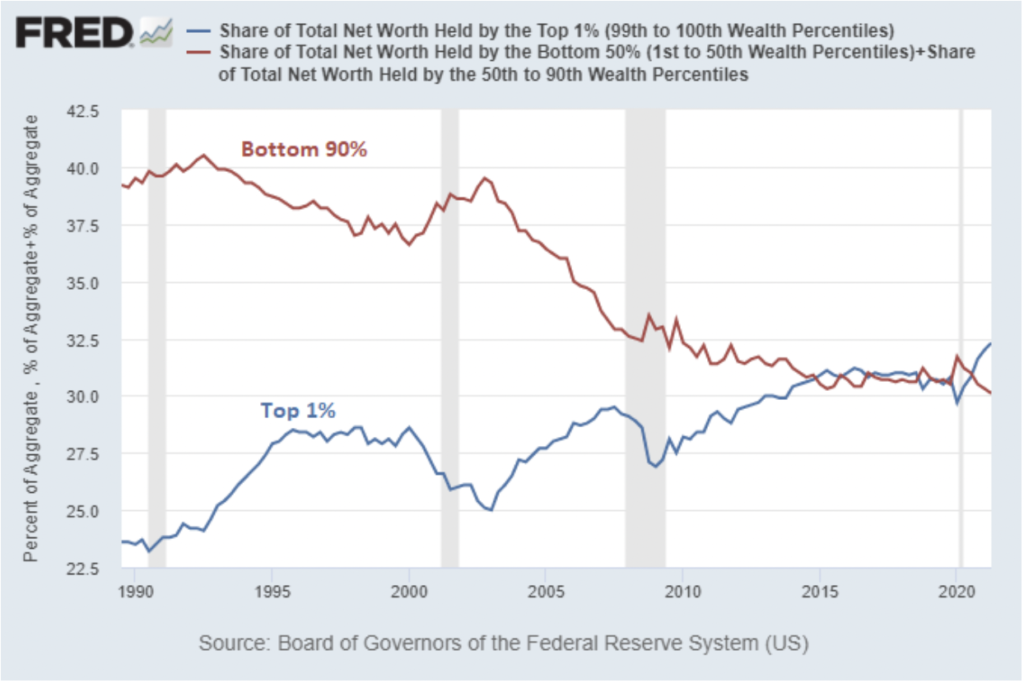

Consider the widening wealth gap in the United States. As the charts below help to enumerate, it seems evident that since our move toward a purely fiat system, the rich have gotten richer and the rest have stayed stagnant.

Chart Source: WTFHappenedIn1971.com

Chart Source: “Does QE Cause Wealth Inequality” by Lyn Alden

Data Source: St. Louis Fed

The factors contributing to the wealth inequality are undeniably multifaceted and complex, but it’s my suggestion that the architecture of our fiat monetary system, as well as the increasingly rampant monetary and fiscal policies it enables, have contributed to broad financial instability and inequality. Let’s look at a couple examples of imbalances resulting from centrally controlled government money, ones that are particularly applicable to the middle and lower classes.

The Reserve Currency Complication

The U.S. Dollar sits at the base of the 21st century fiat monetary system as the global reserve currency. The march toward dollar hegemony as we know it today has taken place incrementally over the last century, with key developments along the way including the Bretton Woods Agreement post WWII, the severance of the dollar from gold in 1971, and the advent of the Petrodollar in the mid 1970s, all of which helped move the monetary base layer away from more internationally neutral assets — such as gold — toward more centrally controlled assets, namely government debt. United States liabilities are now the foundation of today’s global economic machine3; U.S. treasuries are today’s reserve asset of choice internationally. Reserve currency status has its benefits and tradeoffs, but in particular, it seems this arrangement has had negative impacts on the livelihood and competitiveness of U.S. industry and manufacturing — the American working class. Here is the logical progression that leads me (and many others) to this conclusion:

- A reserve currency (the U.S. dollar in this case) remains in comparatively constant high demand since all global economic players need dollars to participate in international markets. One could say a reserve currency remains perpetually expensive.

- This indefinitely and artificially elevated exchange rate means the buying power for citizens in a country with reserve currency status stays comparatively strong, while the selling power stays comparatively diminished. Hence, imports grow and exports fall, causing persistent trade deficits (this is known as the Triffin Dilemma).

- As a result, domestic manufacturing becomes relatively expensive while international alternatives become cheap, which leads to an offshoring and hollowing out of the labor force — the working class.

- All the while, those benefiting most from this reserve status are the ones playing part in an increasingly engorged financial sector and/or involved in white collar industries like the tech sector that benefit from diminished production costs as a result of cheap offshore manufacturing and labor.

The reserve currency dilemma highlighted above leads to exorbitant privilege for some and inordinate misfortune for others4. And let’s once again go back to the root of the issue: unsound and centrally controlled fiat money. The existence of reserve fiat currencies at the base of our global financial system is a direct consequence of the world moving away from more sound, internationally neutral forms of value denomination.

The Cantillon Conundrum

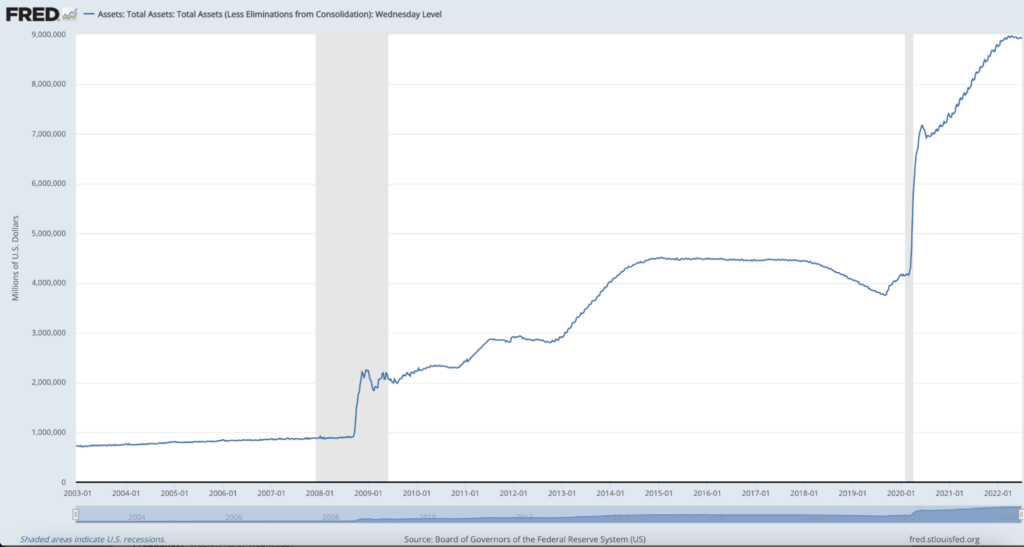

Fiat money also sows the seeds of economic instability and inequality by actuating monetary and fiscal policy interventions, or as I’ll refer to them here, monetary manipulations. Money that is centrally controlled can be centrally manipulated, and although these manipulations are enacted to keep the brittle economic machine churning (like we talked about above during the GFC), they come with consequences. When central banks and central governments spend money they don’t have and insert liquidy whenever they deem it necessary, distortions occur. We get a glimpse at the sheer magnitude of recent centralized monetary manipulation by glancing at the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. It’s gone bananas in recent decades, with less than $1 trillion on the books pre-2008 and fast approaching $9 trillion today.

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

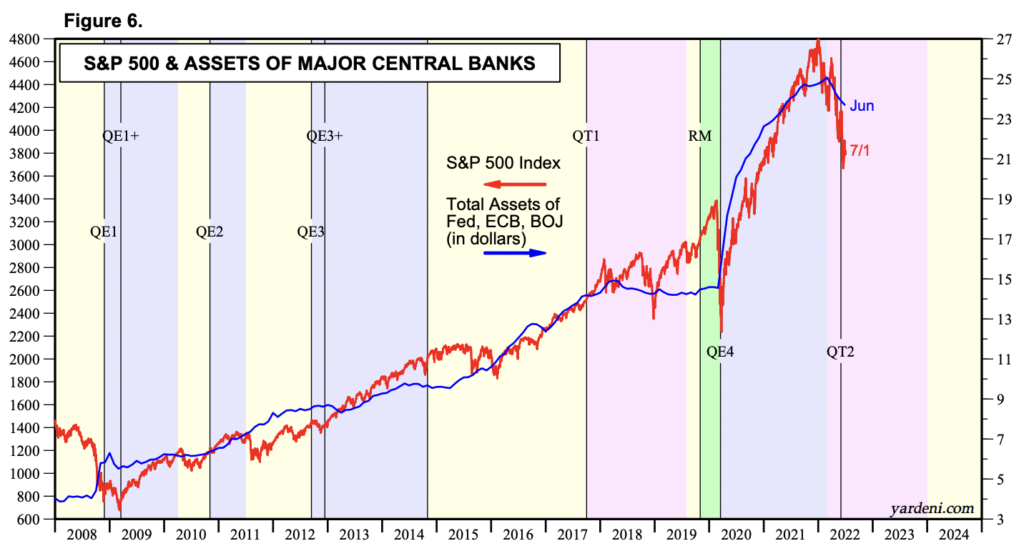

The Fed’s ballooning balance sheet shown above includes assets like treasury securities and mortgage backed securities. A large portion of these assets were acquired with money (or reserves) created out of thin air through a form of monetary policy known as quantitative easing (QE). The effects of this monetary fabrication are hotly debated in economic circles, and rightfully so. Admittedly, depictions of QE as “money printing” are shortcuts that disregard the nuance and complexity of these nifty tactics5; nonetheless, these descriptions may, in many regards, be directionally accurate. What’s clear is that this massive amount of “demand” and liquidity coming from central banks and governments has had a profound effect on our financial system; in particular, it seems to boost asset prices. Correlation doesn’t always mean causation, but it gives us a place to start. Check out this chart below, which trends the stock market (in this case the S&P 500) with the balance sheets of major central banks.

Chart Source: Yardini Research, Inc (credit to Preston Pysh for pointing this chart out in this tweet)

Whether it’s heightening the upside or limiting the downside, expansionary monetary policies seem to cushion elevated asset values. It may appear counterintuitive to highlight asset price inflation during a significant market crash — at time of writing the S&P 500 is down close to 20% from an all time high, and the Fed looks slower to step in due to inflationary pressures. Nevertheless, there still remains a point at which policymakers have rescued, and will continue to rescue, markets and/or pivotal financial institutions undergoing intolerable distress — true price discovery is constrained to the downside. Chartered Financial Analyst and former hedge fund manager James Lavish spells this out well:

“When the Fed lowers interest rates, buys US Treasuries at high prices, and lends money indefinitely to banks, this injects a certain amount of liquidity into the markets and helps shore up the prices of all the assets that have sharply sold off. The Fed has, in effect, provided the markets with downside protection, or a put to the owners of the assets. Problem is, the Fed has stepped in so many times recently, that markets have come to expect them to act as a financial backstop, helping prevent an asset price meltdown or even natural losses for investors.”6

Evidence suggests that supporting, backstopping, and/or bailing out key financial players keeps asset prices artificially stable and, in many environments, soaring. This is a manifestation of the Cantillon Effect, the idea that the centralized and uneven expansion of money and liquidity benefits those closest to the money spigot. Erik Yakes describes this dynamic succinctly in his book The 7th Property:

“Those who are furthest removed from interaction with financial institutions end up worst off. This group is typically the poorest in society. Thus, the ultimate impact on society is a wealth transfer to the wealthy. Poor people become poorer, while the wealthy get wealthier, resulting in the crippling or destruction of the middle class.”

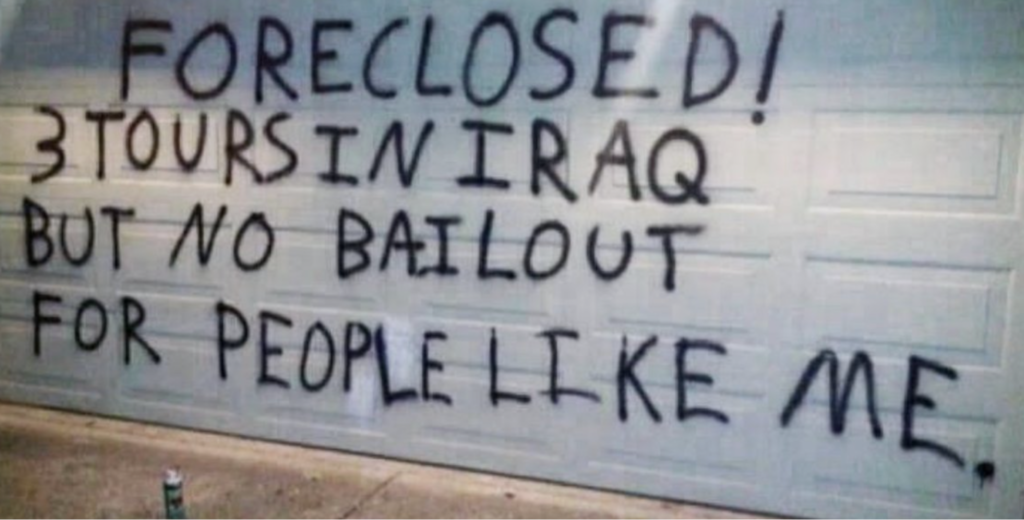

When money is fabricated out of thin air, it’s prone to bolster asset valuations; therefore, the holders of those assets benefit. And who holds the largest quantity and highest quality of assets? — the wealthy. Monetary manipulation tactics seem to cut primarily one way. Let’s again consider the GFC. A popular narrative that I believe is at least partially correct depicts average wage earners and homeowners largely left to fend for themselves in 2008 — foreclosures and job losses were plentiful; meanwhile, insolvent financial institutions were enabled to march on and eventually recover.

Image Source: Tweet from Lawrence Lepard

If we fast forward to the COVID-19 fiscal and monetary responses, I can hear counterarguments stemming from the notion that stimulus money was widely distributed from the bottom up. This is partially true, but consider that $1.8 trillion went to individuals and families in the form of stimulus checks, while the chart above reveals that the Fed’s balance sheet has expanded by roughly $5 trillion since the start of the pandemic. Much of this difference entered the system elsewhere, assisting banks, financial institutions, businesses, and mortgages. This has, at least partially, contributed to asset price inflation. If you are an asset holder, you can see evidence of this in recalling that your portfolio and/or home valuations were likely at all-time highs amidst one of the most economically damaging environments in recent history: a pandemic with globally mandated shutdowns.7

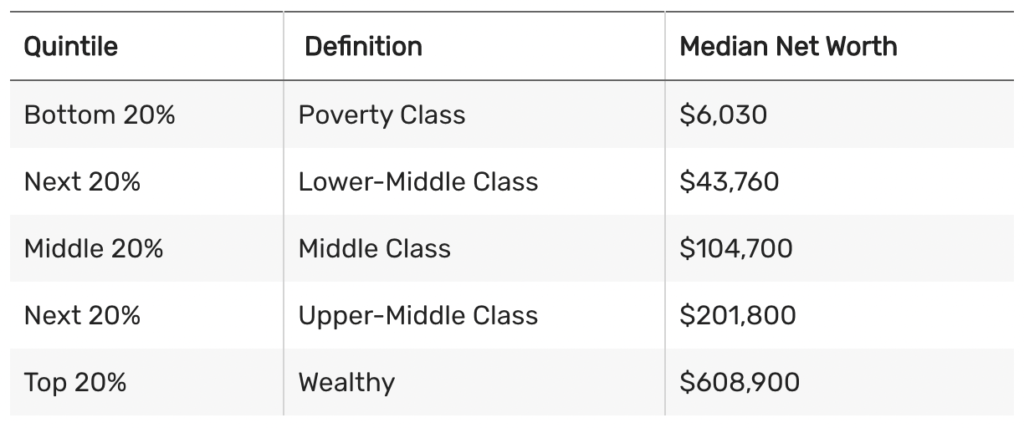

In fairness, many members of the middle class are asset holders themselves, and a good portion of the Fed’s balance sheet expansion went to buying mortgage bonds, which helped lower the cost of mortgages for all. But let’s consider that in America, the median net worth is just $122,000, and as the chart below catalogs, this number plummets as we move down the wealth spectrum.

Chart Source: TheBalance.com

Furthermore, nearly 35% of the population doesn’t own a home, and let’s also discern that the type of real estate owned is a key distinction — the wealthier people are, the more valuable their real estate and correlated appreciation becomes. Asset inflation disproportionately benefits those with more wealth, and as we explored already, wealth concentration has grown more and more pronounced in recent years and decades. Macroeconomist Lyn Alden elaborates on this concept:

“Asset price inflation often happens during periods of high wealth concentration and low interest rates. If a lot of new money is created, but that money gets concentrated in the upper echelons of society for one reason or another, then that money can’t really affect consumer prices too much but instead can lead to speculation and overpriced buying of financial assets. Due to tax policies, automation, offshoring, and other factors, wealth has concentrated towards the top in the US in recent decades. People in the bottom 90% of the income spectrum used to have about 40% of US household net worth in 1990, but more recently it’s down to 30%. The top 10% folks saw their share of wealth climb from 60% to 70% during that time. When broad money goes up a lot but gets rather concentrated, then the link between broad money growth and CPI growth can weaken, while the link between broad money growth and asset price growth intensifies.”8

As a whole, artificially inflated asset prices are maintaining or increasing the purchasing power of the wealthy, while leaving the middle and lower classes stagnant or in decline. This also holds true for members of younger generations who have no nest egg and are working to get their financial feet underneath them. Although WILDLY imperfect (and many would suggest detrimental), it’s understandable why more and more people are clamoring for things like universal basic income (UBI). Handouts and redistributive economic approaches are increasingly popular for a reason. Poignant examples do exist where the rich powerful were advantaged above the average Joe. Preston Pysh, co-founder of The Investor’s Podcast Network, has described certain expansionary monetary policies as “universal basic income for the rich.”9 In my view, it’s ironic that many of those privileged to have benefited most dramatically from the current system are also those who advocate for less and less government involvement. These individuals fail to recognize that existing central bank interventions are a major contributing factor to their bloated wealth (in the form of assets). Many are blind to the fact that they are the ones suckling from the largest government teat in the world today: the fiat money creator. I am certainly not an advocate for rampant handouts or suffocating redistribution, but if we want to preserve and grow a robust and functional form of capitalism, it must enable equal opportunity and fair value accrual. This seems to be breaking down as the world’s monetary base layer becomes more unsound. It’s quite clear that the current setup is not distributing milk evenly, which begs the question: do we need a new cow?

Overarchingly, I believe many average folks are encumbered by 21st century economic architecture. We need an upgrade, a system that can be concurrently antifragile and equitable. The bad news is that within the existing setup, the trends I’ve outlined above show no signs of abatement, in fact they are bound to worsen. The good news is that the incumbent system is being challenged by a bright orange newcomer. In the remainder of this essay we will unpack why and how Bitcoin functions as a financial equalizer. For those stuck in the proverbial economic basement, dealing with the cold and wet consequences of deteriorating financial plumbing, Bitcoin provides several key remedies to current fiat malfunctions. We’ll explore these remedies in Part 2 and Part 3.

PART 2: The Purchasing Power Preserver

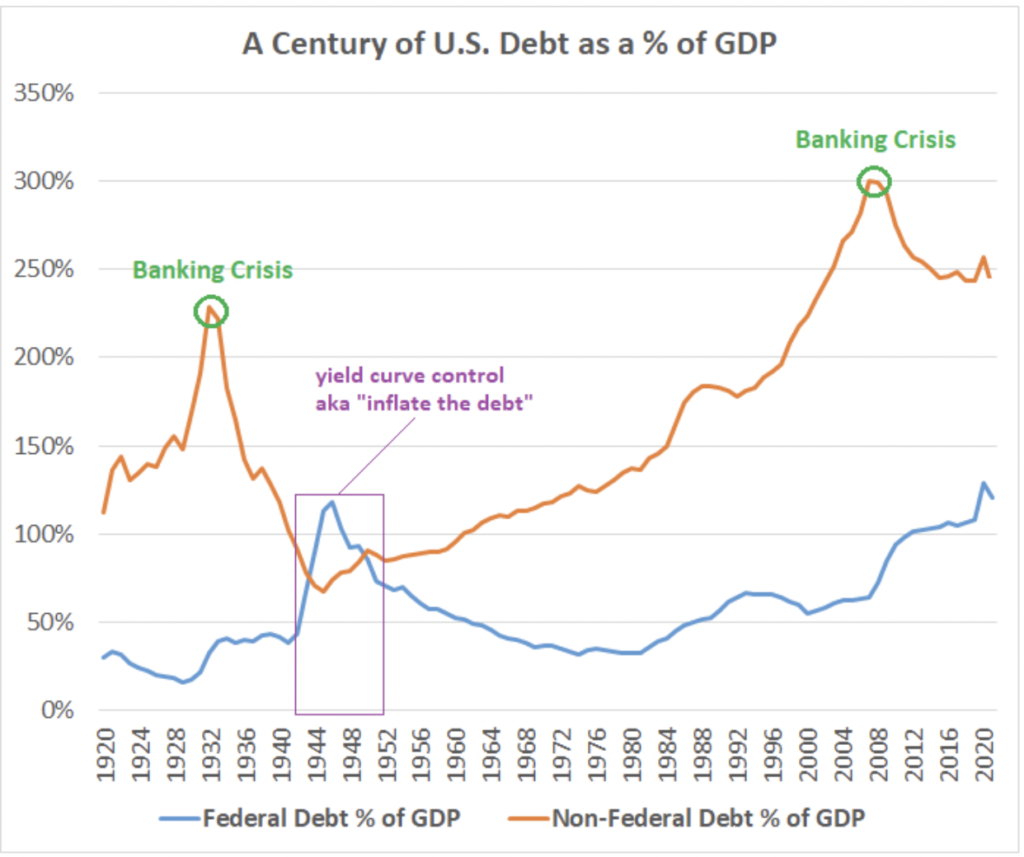

Unprecedented debt levels that exist in today’s financial system spell one thing in the long run: currency debasement. The word “inflation” is tossed around frequently and flippantly these days. Few appreciate its actual meaning, true causes, or real implications. For many, inflation is nothing more than a price at the gas pump or grocery store that they like to bitch about over wine and cocktails. “It’s Biden’s, Obama’s or Putin’s fault!” When we zoom out and think long-term, inflation is a massive (and I argue unsolvable) fiat math problem that gets tougher and tougher to reconcile as decades march on. In today’s economy, productivity lags debt to such an extent that any and all methods of restitution require struggle. A key metric for tracking debt progression is debt divided by gross domestic product (Debt/GDP). Digest the chart below which specifically reflects both total debt and public federal debt as relates to GDP.

Chart Source: “Does the National Debt Matter” by Lyn Alden

Data Source: St. Louis Fed

If we focus on federal debt (blue line), we see that in just 50 years, we’ve gone from sub 40% Debt/GDP to 135% during the COVID-19 pandemic — the highest levels of the last century. It’s also worth noting that the current predicament is significantly more dramatic than even this chart and these numbers indicate, since this doesn’t reflect colossal unfunded entitlement liabilities (i.e. Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid) that are anticipated in perpetuity.

What does this excessive debt mean? To make sense of it, let’s distill these realities down to the individual. Suppose someone racks up exorbitant liabilities — two mortgages well outside their price range, three cars they can’t afford, and a boat they never use. Even if their income is sizable, eventually their debt load reaches a level they cannot sustain. Maybe they procrastinate by tallying up credit cards or taking out a loan with a local credit union to merely service the minimum payments on their existing debt, but if these habits persist, the camel’s back inevitably breaks — they foreclose on the homes; SeaRay sends someone to remove the boat out of their driveway; their Tesla gets repossessed; they go bankrupt. No matter how much she or he felt like they “needed” or “deserved” all those items, the math finally bit them in the ass. If you were to create a chart to encapsulate this person’s quandary, you would see two lines diverging in opposite directions. The gap between the line representing their debt and the line representing their income (or productivity) would widen until they reached insolvency. The chart would look something like this:

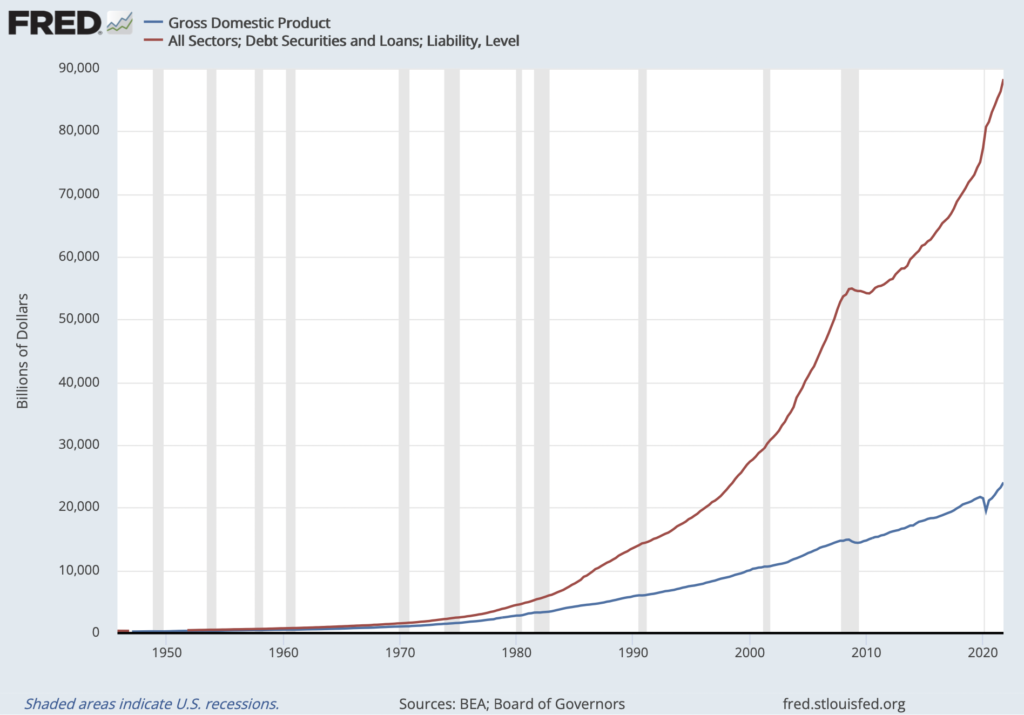

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

And yes, this chart is real. It’s a distillation of United States’ total debt (in red) over gross domestic product, or productivity (in blue). I first saw this chart posted on Twitter by well-known sound money and tech investor Lawrence Lepard. He included the following text above it.

“Blue line generates income to pay interest on red line. See the problem? It’s just math.”

The math is catching up to sovereign nation states too, but the way the chickens come home to roost looks quite different for central governments than for the individual in the paragraph above, particularly in countries with reserve currency status. You see, when a government has its paws on both the supply of money and the price of money (i.e. interest rates) as they do in today’s fiat monetary system, they can attempt to “default” in a much softer fashion. This sort of soft default necessarily leads to growth in money supply, because when central banks have access to newly created reserves (a money printer, if you will) it’s incredibly unlikely debt service payments will be missed or neglected. Rather, debt will be monetized, meaning the government will borrow newly fabricated money from the central bank rather than raising authentic capital through increasing taxes or selling bonds to real buyers in the economy (actual domestic or international investors). In this way, money is artificially manufactured to service liabilities. Lyn Alden puts debt levels and debt monetization in context:

“When a country starts getting to about 100% debt-to-GDP, the situation becomes nearly unrecoverable . . . a study by Hirschman Capital noted that out of 51 cases of government debt breaking above 130% of GDP since 1800, 50 governments have defaulted. The only exception, so far, is Japan, which is the largest creditor nation in the world. By “defaulted”, Hirschman Capital included nominal default and major inflations where the bondholders failed to be paid back by a wide margin on an inflation-adjusted basis. . . . There’s no example I can find of a large country with more than 100% government debt-to-GDP where the central bank doesn’t own a significant chunk of that debt.”11

The inordinate monetary power of fiat central banks and treasuries is a large contributor to the excessive leverage (debt) buildup in the first place. Centralized control over money enables policy makers to delay economic pain in a seemingly perpetual manner, repeatedly alleviating short-term problems. But even if intentions are pure, this game cannot last forever. History demonstrates that good intentions are not enough — if incentives are improperly aligned, instability awaits.

Lamentably, the threat of harmful currency debasement and inflation dramatically increases as debt levels become more unsustainable. In the 2020s, we are beginning to feel the damaging effects of this shortsighted fiat experiment. Those who exert monetary power do indeed have the ability to palliate pressing economic pain, but in the long run it’s my contention that this will amplify total economic destruction, particularly for the less privileged in society. As more monetary units enter the system to ease discomfort, existing units lose purchasing power relative to what would have transpired without such money insertion. Pressure eventually builds up in the system to such an extent that it must escape somewhere — that escape valve is the debasing currency. Career-long bond trader Greg Foss puts it like this:

“In a debt/GDP spiral, the fiat currency is the error term. That is pure mathematics. It is a spiral to which there is no mathematical escape.”12

This inflationary landscape is especially troublesome to members of the middle and lower classes for several key reasons. First, as we talked about above, this demographic tends to hold fewer assets, both in total and as a percentage of their net worth. As the currency melts, assets like stocks and real estate tend to rise (at least somewhat) alongside money supply. Conversely, growth in salaries and wages is likely to underperform inflation, and those with less free cash quickly start treading water. (This was covered at length in Part 1.) Second, middle and lower class members are, by and large, demonstrably less financially literate and nimble. In inflationary environments knowledge and access are power, and it often takes maneuvering to maintain buying power. Members of the upper class are far more likely to have the tax and investment know-how, as well as egress into choice financial instruments, to jump on the life raft as the ship goes down. Third, many average wage earners are more reliant on defined benefit plans, social security, or traditional retirement strategies — these tools stand squarely in the scope of the inflationary firing squad. During periods of debasement, assets with payouts expressly denominated in the inflating fiat currency are most vulnerable. The financial future of many average folks is heavily reliant on one of the following:

- Nothing. They are not saving and investing and are therefore maximally exposed to currency debasement.

- Social security, which is the world’s largest ponzi scheme and very well may not exist for more than a decade or two. If it does hold up, it will be paid out in debasing fiat currency.

- Other defined benefit plans such as pensions or annuities. Once again, the payouts of these assets are defined in fiat terms. Additionally, they often have large amounts of fixed income exposure (bonds) with yields denominated in fiat currency.

- Retirement portfolios or brokerage accounts with a risk profile that has worked for the last forty years but is unlikely to work for the next forty. These fund allocations often include escalating exposure to bonds for “safety” as investors age (risk parity). Unfortunately, this attempt at risk mitigation makes these folks increasingly reliant on dollar denominated fixed income securities and, therefore, debasement risk. Most of these individuals will not be nimble enough to pivot in time to retain buying power.

The lesson here is that the everyday worker and investor is in desperate need of a useful and accessible tool that excludes the error term in the fiat debt equation. I am here to argue that nothing serves this purpose more marvelously than Bitcoin. Although much remains unknown about this protocol’s pseudonymous founder, Satoshi Nakamoto, his motivation for unleashing this tool was no mystery. In the genesis block, the first Bitcoin block ever mined on January 3, 2009, Satoshi highlighted his disdain for centralized monetary manipulation and control by embedding a recent London Times cover story:

“The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.”

The motivations behind Bitcoin’s creation were certainly multifaceted, but it seems evident that one of, if not the, primary problem Satoshi set out to solve was that of unchangeable monetary policy. As I write this today, some thirteen years since the release of this first block, this goal has been unceasingly achieved. Bitcoin stands alone as the first ever manifestation of enduring digital scarcity and monetary immutability — a protocol enforcing a dependable supply schedule by way of a decentralized mint, powered by harnessing real world energy via Bitcoin mining and verified by a globally distributed, radically decentralized network of nodes. Roughly 19 million BTC exist today, and no more than 21 million will ever exist. Bitcoin is conclusive monetary reliability — the antithesis of, and alternative to, debasing fiat currency. Nothing like it has ever existed, and I believe its emergence is timely for much of humanity.

Bitcoin is a profound gift to the world’s financially marginalized. With a small amount of knowledge and a smartphone, members of the middle and lower class, as well as those outside the first world and the billions who remain unbanked, now have a reliable place holder for their hard earned capital. Greg Foss often describes Bitcoin as “portfolio insurance,” or as I’ll call it here, hard work insurance. Buying Bitcoin is a working man’s exit from a fiat monetary network that guarantees depletion of his capital into one that mathematically and cryptographically assures his supply stake. It’s the hardest money mankind has ever seen, competing with some of the softest monies in human history. I encourage readers to heed the words of Saifedean Ammous from his seminal book The Bitcoin Standard:

“History shows it is not possible to insulate yourself from the consequences of others holding money that is harder than yours.”

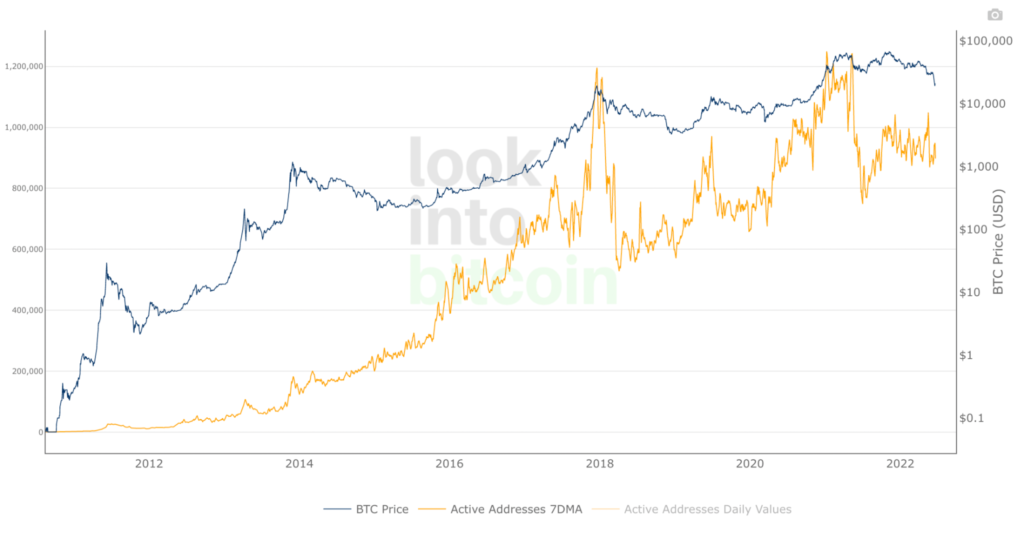

On a zoomed out timeframe, Bitcoin is built to preserve buying power. However, those who choose to participate earlier in its adoption curve serve to the benefit the most. Few understand the implications of what transpires when exponentially growing network effects meet a monetary protocol with absolute supply inelasticity. (Hint: it might continue to look something like the chart below.)

Chart Source: LookIntoBitcoin.com

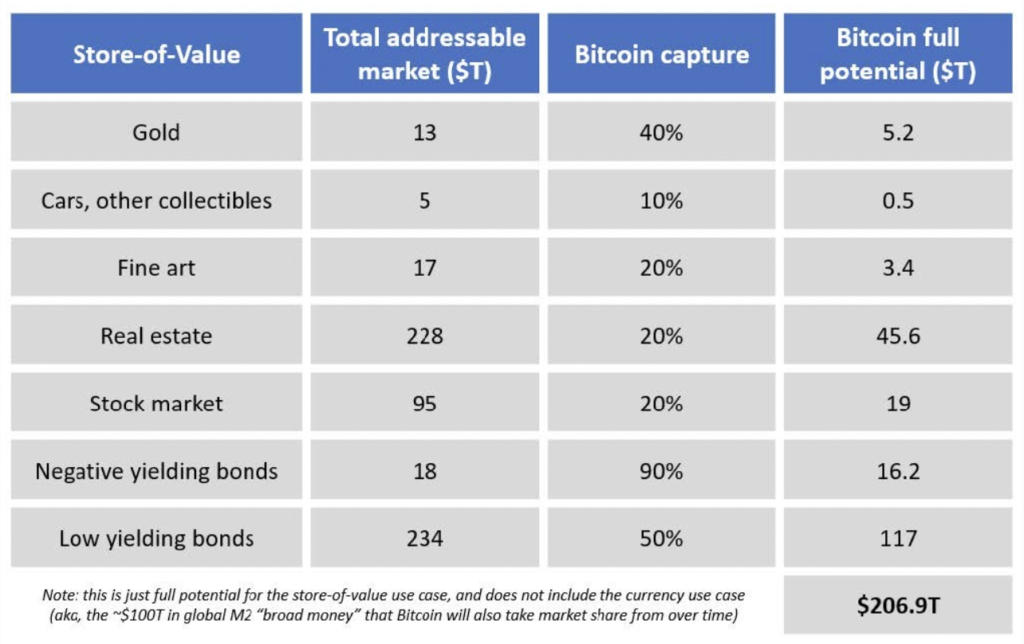

Bitcoin has the makings of an innovation that’s time has come. The apparent impenetrability of its monetary architecture contrasted with today’s economic plumbing in tremendous disrepair indicates that incentives are aligned for the fuse to meet the dynamite. Bitcoin is arguably the soundest monetary technology ever discovered, and its advent aligns with the end of a long-term debt cycle when hard assets will plausibly be in highest demand. It’s poised to catch much of the air escaping the balloons of a number of overly monetized13 asset classes, including low to negative yielding debt, real estate, gold, art & collectibles, offshore banking, and equity.

Image Source: “Am I Too Late for Bitcoin” by @Croesus_BTC

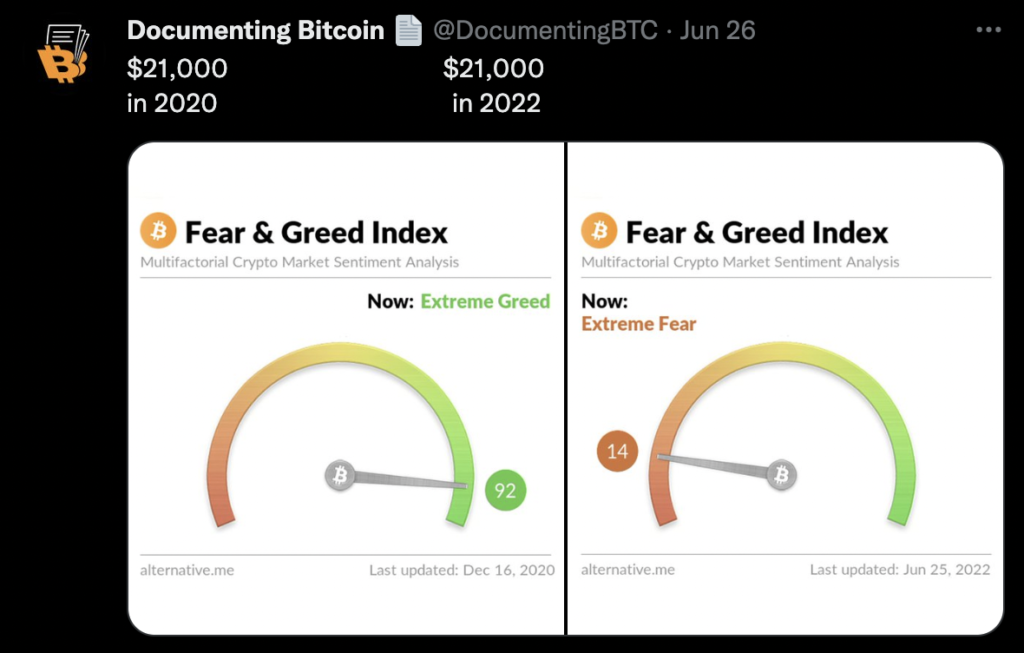

It’s here where I can sympathize with the eye rolls or chuckles from the portion of the readership who point out that, in our current environment (July 2022), the price of Bitcoin has plummeted amidst high CPI prints (high inflation). But I suggest we be careful and zoom out. Today’s capitulation was pure euphoria a little over two years ago. Bitcoin has been declared “dead” over and over again through the years, only for this possum to re-emerge larger and healthier. In fairly short order, a similar BTC price point can represent both extreme greed and subsequently extreme fear on its road to escalating value capture.

Image Source: Tweet by @DocumentingBTC

History shows us that technologies with strong network effects and profound utility (a category I believe Bitcoin fits in) have a way of gaining enormous adoption right underneath humanity’s nose without most fully recognizing it.

Image Source: Regia Marinho on Medium

The following excerpt from Vijay Boyapati’s well known “Bullish Case for Bitcoin” essay14 explains this well, particularly in relation to monetary technologies:

“When the purchasing power of a monetary good increases with increasing adoption, market expectations of what constitutes “cheap” and “expensive” shift accordingly. Similarly, when the price of a monetary good crashes, expectations can switch to a general belief that prior prices were “irrational” or overly inflated. . . . The truth is that the notions of “cheap” and “expensive” are essentially meaningless in reference to monetary goods. The price of a monetary good is not a reflection of its cash flow or how useful it is but, rather, is a measure of how widely adopted it has become for the various roles of money.”

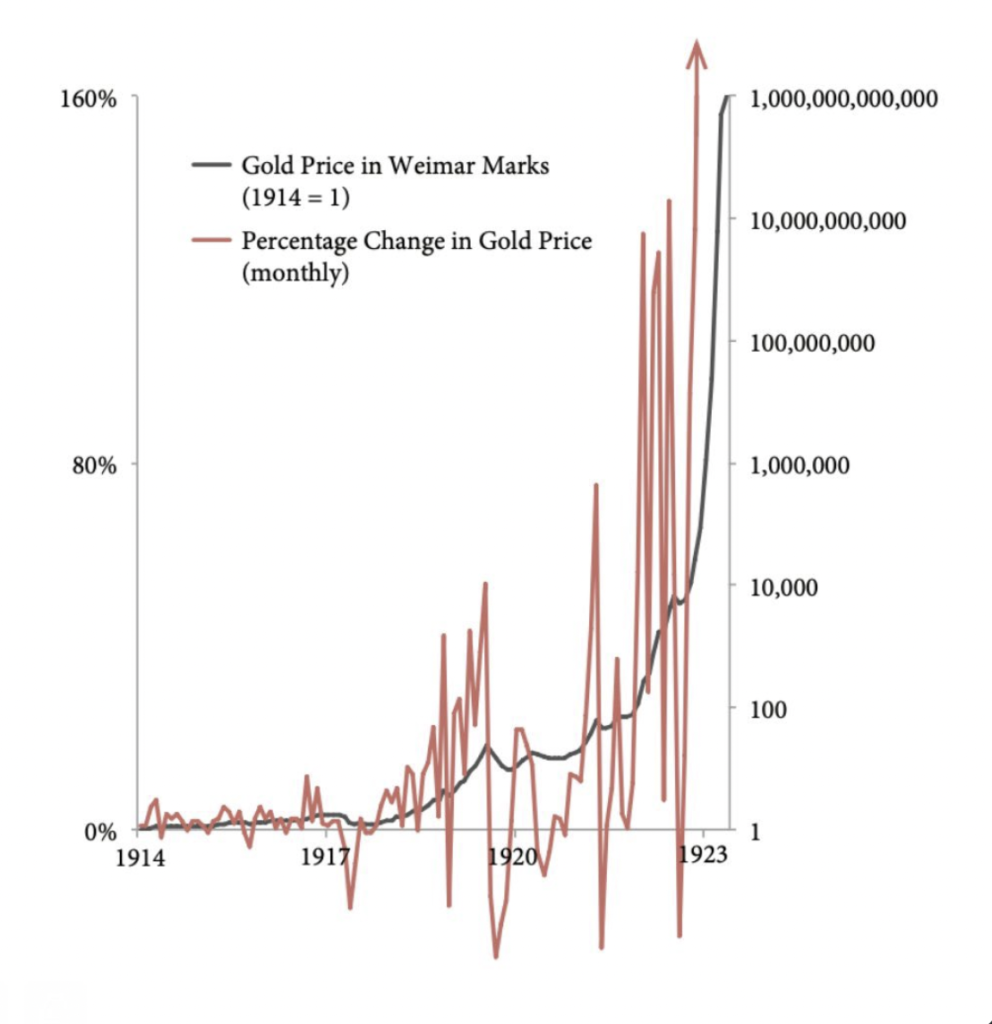

If Bitcoin does one day accrue enormous value the way I’ve suggested it might, its upward trajectory will be anything but smooth. First consider that the economy as a whole is likely to be increasingly unstable moving forward — systemically fragile markets underpinned by credit have a propensity to be volatile (to the DOWNSIDE in the long run against hard assets). Promises built on promises can quickly fall like dominoes, and in the last few decades we’ve experienced increasingly regular and significant deflationary episodes (often followed by stunning recoveries assisted by fiscal and monetary intervention). Amidst an overall backdrop of inflation, there will be fits of dollar strengthening — we are experiencing one currently. Now add in the fact that, at this stage, Bitcoin is nascent; it’s poorly understood; its supply is completely unresponsive (inelastic); and, in the minds of most big financial players, it’s optional and speculative. As I write this, Bitcoin is nearly 70% down from an all time high of $69,000, and in all likelihood, it will be extremely volatile for some time. However, the key distinction is that BTC has been, and in my view will continue to be, volatile to the UPSIDE in relation to soft assets (those with a subjective and expanding supply schedules [i.e. fiat]). When talking about forms of money, the words “sound” and “stable” are far from synonymous. I can’t think of a better example of this dynamic at work than gold versus the German papiermark during the hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic. Soak in the chart below to see how tremendously volatile gold was during this period.

Chart Source: originally produced by Daniel Oliver Jr. and later tweeted out by Lawrence Lepard

Dylan LeClair has said the following in relation to the chart above:

“You’ll often see charts from Weimar Germany of gold priced in the paper mark going parabolic. What that chart doesn’t show is the sharp drawdowns & volatility that occurred during the hyper-inflationary period. Speculating using leverage got wiped out multiple times.”

Despite the papiermark inflating completely away in relation to gold over the long run, there were periods where the mark significantly outpaced gold. My base case is that Bitcoin will continue to do something akin to this in relation to the world’s contemporary basket of fiat currencies.

Ultimately, the proposition of Bitcoin bulls like myself is that the addressable market of this asset is mind numbing. Staking a claim on even a small portion of this network may allow members of the middle and lower classes to power on the sump pump and keep the basement dry. My plan is to accumulate BTC, batten down the hatches, and hold on tight with low time preference. I’ll close this part with the words of Dr. Jeff Ross, former interventional radiologist turned hedge fund manager:

“Checking and savings accounts are where your money goes to die; bonds are return-free risk. We have a chance now to exchange our dollar for the greatest sound money, the greatest savings technology, that has ever existed.”15

In Part 3, we’ll explore two more key ways in which Bitcoin works to rectify existing economic imbalances.

PART 3: Monetary Decomplexification

The Financial Simplifier

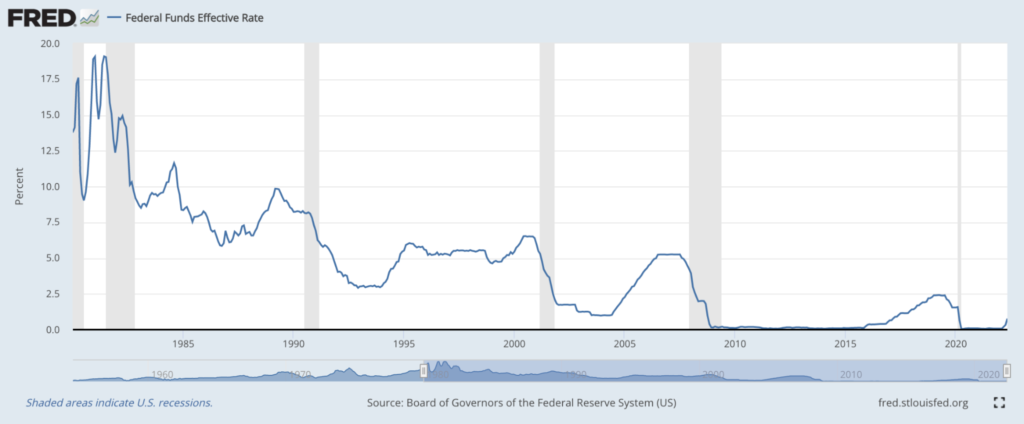

Our current financial system is extraordinarily complicated, and this complication inhibits the participation and success of those who are less financially literate. Preparing for the financial future is overwhelming for many (if not most) everyday folks. One might ask why our current system is so complex, and part of the answer harkens back to something covered in Part 1 and Part 2 of this essay. We’ve established that a centralized monetary system with fiat as its base invariably leads to increased monetary manipulation. A prominent form of monetary manipulation is influencing interest rates. Short-term interest rates set by central banks are one of the most important inputs in both domestic and international markets (the most influential of which is the federal funds rate set set by the U.S Central Bank, the Federal Reserve Board). These centrally controlled rates dictate the cost for capital at the base of the system, which eventually seeps upward and impacts virtually every asset class, including treasury and credit markets, mortgages, real estate, and eventually equities (stocks). I’ll once again defer to Lyn Alden to sum up the reasoning behind, and impact of, short-term interest rate manipulation:

“This rate [the Fed Funds Rate] trickles up to all other debt classes, strongly affecting them, but indirectly. So, as the Federal Reserve raises or lowers this key rate, it eventually affects treasury bonds, mortgages, corporate bonds, auto loans, margin debt, student debt, and even many foreign bonds. There are other factors that affect interest yields on various debt, but the Federal Funds Rate is one of the most important impacts. The Federal Reserve reduces this rate when it wants to produce “easy money” to stimulate the economy. A low interest rate for all types of debt encourages consumers and businesses to borrow money and use it to consume or expand, which benefits the economy in the short term.”16

In an attempt to boost economic activity and/or mitigate short-term economic discomfort, central banks around the world have demonstrated a historical susceptibility to lower interest rates well beyond where they would have settled naturally. Today, we are staring down the barrel of a 40-year decline in short-term rates to nothing. Below is a chart displaying the movement of the Fed funds rate over the last 40 years.

Char Source: St. Louis Fed

In many parts of the world, rates have even gone below nothing into negative territory. (i.e. negative interest rates). My guess is that if you had told a bond trader thirty years ago that there would one day be trillions of dollars worth of negative nominal-yielding debt instruments, they would have laughed you out of the room — yet here we are. And although causes are multifaceted, it’s hard to deny that prevalent monetary policy, in the form of interest rate manipulation and enabled by fiat fundamentals, is at least partially to blame.

Image/Article Source: The Motley Fool

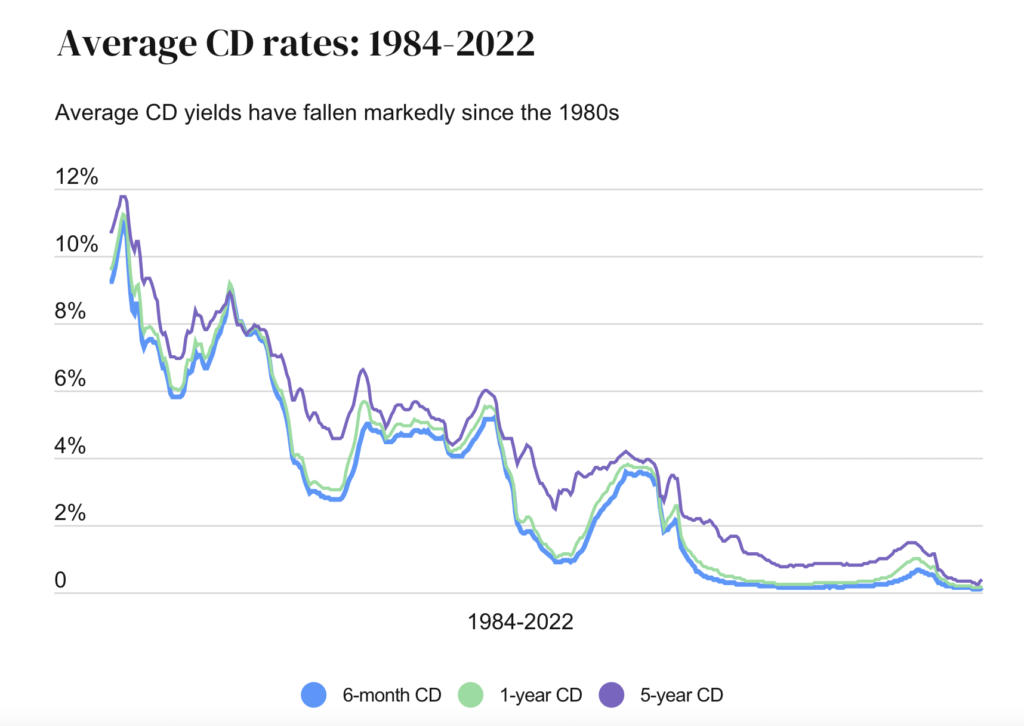

Because the short-term central bank interest rates (“risk free rates”) are artificially suppressed, risk-free returns (or yields) are also suppressed. Consequently, savers and investors looking to grow their capital must get more creative and nimble as well as take on more risk. In 1989 a person could lock money in a certificate of deposit (CD) at their local bank and get a high nominal (and serviceable real) yield. But as the chart below demonstrates, times have changed….immensely.

Chart Source: Bankrate.com

When we consider today’s massive debt levels and correlated risks of debasement, and then combine the fact that low-risk returns on capital are historically diminished, we uncover an issue: low-risk investments actually become risky over time as purchasing power gets depleted. Savers need returns to simply keep up with inflation; they must take on more risk to keep up. The point here is that an inherently and increasingly inflationary money supply demands that people look to escape the money they are paid in. They must go elsewhere to maintain and grow wealth — cash is trash and real yields on assets that were once profitable are now persistently negative. With low-risk yield opportunities diminished, those who want to preserve and grow the buying power of their capital are confronted with three main options:

- Be increasingly agile in managing their own portfolio. They must learn to speak fluent “financialeze” if you will.

- Rely on a professional to handle the complicated financial landscape for them.

- Utilize passive investment vehicles (for example index funds), which expose them to broad, systemic risks. (I am certainly not against passive investing and indexing — I do much of it myself — but the problem is these strategies have largely become synonymous with saving.)

An old tweet by Pierre Rochard highlights this well:

Image/Tweet Source: “Bitcoin is The Great Definancialization” by Parker Lewis

These aforementioned dynamics have led to an engorged financial sector filled with endless planners, managers, brokers, regulators, tax professionals, and intermediaries. The finance and insurance sector has grown from around 4% of GDP in 1970 to close to 8% of GDP today.17 An enormous amount of slop has been tossed into the pig pen, and the hogs are feeding. Can you blame them? Don’t misunderstand me; I am not against the financial sector in totality, and I do believe that even if Bitcoin is the monetary standard of the future, financial services will remain prevalent and important. (Although their role will change, they will look much different, and I believe more consumers will demand transparency and auditability like proof of reserves.18) But what does seem clearly imbalanced is the sheer size of today’s financial sector. In his article “The Great De-Financialization”, Parker Lewis wonderfully summarizes the impetus behind this dynamic:

“Financialization has turned retirement savers into perpetual risk-takers and the consequence is that financial investing has become a second full-time job for many, if not most. Financialization has been so errantly normalized that the lines between saving (not taking risk) and investing (taking risk) have become blurred to the extent that most people think of the two activities as being one in the same. Believing that financial engineering is a necessary path to a happy retirement might lack common sense, but it is conventional wisdom.”

Imagine if there was a place where people were simply able to store, preserve, and grow their hard earned capital without risk or need of expertise? This sounds startlingly simple, and some would say far-fetched — in fact, many money managers would shudder at such a prospect, since a complicated investment landscape is a key driver of their usefulness. Gold once served this purpose, and in certain times and places of the past a blacksmith or farmer could reliably maintain purchasing power in a precious metal. But as the centuries wore on and economies of scale grew larger and more global, the velocity of money grew exponentially and the weaknesses of traditionally hard monies like gold became a hindrance — namely the weaknesses of portability and divisibility20. This dynamic necessitated nascent monetary technologies and gave rise to paper currencies backed by gold, then eventually backed by nation state promises — fiat as we know it today.

An investigation of Bitcoin invariably thrusts the learner into an exploration of the characteristics of money itself. For many, this journey leads to the recognition that Bitcoin harnesses and improves on gold’s timeless store of value strength: scarcity, while also rectifying (and many would argue perfecting) gold’s shortcomings of portability and divisibility. Bitcoin mitigates the inherent limitations of traditionally sound stores of value while also harboring the potential to meet today’s monetary velocity needs as a medium of exchange. For this reason it has entered the contemporary financial whirlwind as a great decomplexifier. It introduces a natively digital token with immediate cash finality, while simultaneously assuring holders of a fixed supply by way of a decentralized ledger. BTC is also the first ever digital bearer asset, and it can be self custodied with no counterparty risk. This is a tremendously underappreciated feature, especially in high debt environments where the financial stack is based on increasingly vulnerable promises.20

Architecturally, Bitcoin may be the best money our species has ever had, and unlike gold, it’s built for the 21st century. If you own Bitcoin, you are mathematically, cryptographically, and verifiably guaranteed to maintain a certain size stake in the network — your piece of the pie is set in stone. This single digital asset is equipped to buy gum at the grocery store while simultaneously resting at the very base of the financial system in sovereign wealth funds, in both cases with no intermediary or counterparty risk. Bitcoin is a form of money that can do it all.21

As a result, Bitcoin simplifies the investment landscape for the average individual. Instead of perpetual confusion regarding appropriate investment strategies, average wage earners can allot at least a portion of their capital to the best savings technology ever discovered — a network specifically designed to counter the assured debasement of existing fiat units and the risks of exposure to investments like equity, fixed income, and real estate (if that risk is unwanted by savers).22 Some laugh when Bitcoin is described as a “safe haven asset,” but it is important to remember that volatility and risk are not the same thing.23 BTC has been incredibly volatile while also generating more alpha and than almost any asset on the planet over the last decade. At this date and time, Bitcoin is largely a “risk-on” asset, coupled to the NASDAQ and broader stock market, but I agree with hedge fund manager Jeff Ross when he states:

“At some point in the future, Bitcoin will be seen as the ultimate ‘risk-off’ asset.”24

As liquidity in the Bitcoin network continues growing exponentially, I believe we will see more and more capital flood into BTC rather than cash, treasuries, and gold during periods of economic uncertainty and distress. The game theory suggests that the world will wake up to the best and hardest form of money available, and therefore economic participants will increasingly denominate goods and services in it. As that trend continues, Bitcoin is likely to become an all-weather asset with the ability to perform in a variety of economic environments. This is the beauty of an inherently deflationary25 store of value that can also function as a unit of account and medium of exchange. Bitcoin could become a one-stop-shop for the everyday wage earner — something they may one day get paid with, buy goods and services with, and store wealth in without fear of purchasing power depletion. The BTC network is developing into the ultimate financial simplifier, depriving centralized policy makers the ability to siphon capital out of the hands of those who don’t know how to play the financial game. Bitcoin is monetizing in a parabolic fashion before our eyes, and for those motivated and privileged enough to recognize the fundamentals driving it, this protocol represents an unparalleled wealth preservation mechanism — a direct foil to the fiat ponzi. As a result, middle and lower class basement dwellers, knee deep in leakage, who elect to protect themselves with Bitcoin will very likely find themselves above grade in the long run.

The Debt Disincentivizer

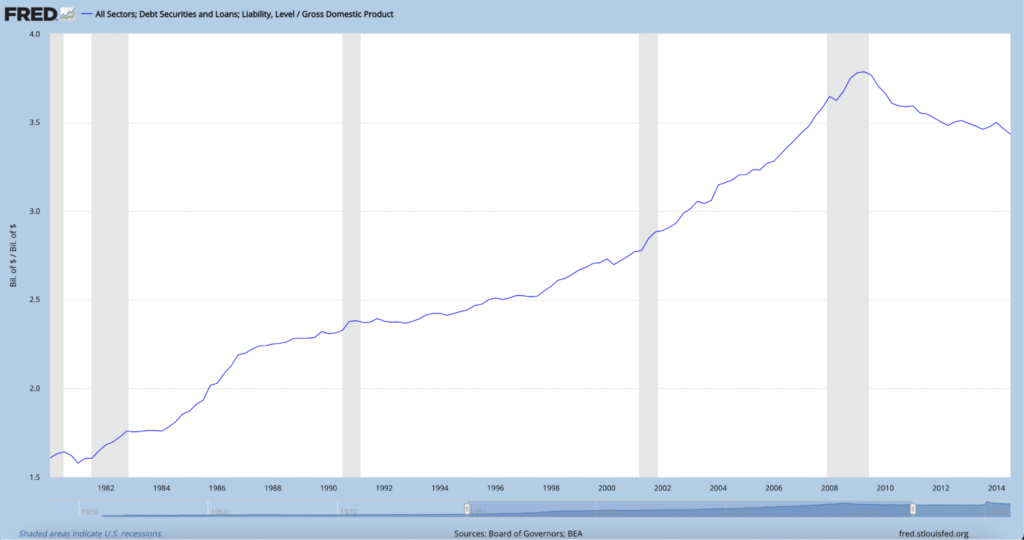

In Part 2 we established that the economy as a whole is heavily indebted, but let’s take another look at debt as compared to gross domestic product (Debt/GDP). The chart below trends all types of U.S. debt (total debt) as a multiple of GDP.

Chart Source: St. Louis Fed

Total U.S. debt is currently 3.5 times that of GDP (or 350%). In comparison, debt was just over 1.5 times that of GDP in 1980, and prior to the Global Financial Crisis, total debt was 3.7 times that of GDP (just slightly higher than where it is today). The system tried to reset and de-lever in 2008, but central banks and governments didn’t fully allow it, and debt remains preposterously high. Why? Because financial policy makers have relied on overused expansionary monetary policies to avoid a deflationary crisis and depressions (policies such as direct interest rate manipulation, quantitative easing, and helicopter money).26 To keep debt from unwinding, new money and/or credit is required. Think about this in terms of the individual: without increasing their income, there is only one way someone can service debts they can’t afford without going bankrupt — take out new debt to pay the old. At a macroeconomic level, unsound money enables this game of “debt balloon” to go on for some time, since the fiat money printer repeatedly assists in mitigating systemic insolvency and contagion. If air is consistently blown into a balloon and never allowed to exit, it simply keeps getting bigger….until it pops. Here’s Lyn Alden summarizing the precariousness of a financial system increasingly built on debt and credit:

“The credit-based global financial system we have constructed and participated in over the past century has to continually grow or die. It’s like a game of musical chairs that we have to keep adding people and chairs to in order for it to never stop. This is because cumulative debts are far larger than the total currency supply, meaning there are more claims for currency than there is currency. As such, too many of those claims can never be allowed to be called in at once; the party must always go on. When debt is too big relative to currency and starts to get called in, new currency is created, since it costs nothing other than some keystrokes to produce.”27

Society has become increasingly accustomed to monetary stimulation. These monetary and fiscal tactics have certainly pulled some growth forward, but much of that expansion is contrived and insubstantial. A steady dose of monetary amphetamine has contributed to a societal addiction to bloated debt and cheap money access. Due to consistent and anticipated backstopping at the monetary foundation, all participants, from nation states to the private sector to the individual, have been structurally enabled to take on more debt and buy more with the credit created while avoiding some of the consequences of poor capital allocation. As a result, malinvestment abounds.

Debt comes in vastly different qualities. Some forms are productive and others are unproductive. Unfortunately, the middle and lower classes tend to be engrossed in much of the latter.28 I often drive around looking at homes and cars in driveways wondering, “How in the blue blazes does everyone afford all this crap?” The older I’ve gotten, the more I’ve recognized that the answer is simple: they can’t. A huge percentage of people are levered up to their eyeballs as a result of buying all kinds of unnecessary stuff they can’t afford. We live in an incessant consumer culture where middle class folks often deem it normal to live an upper class lifestyle; ergo, they end up with minimal free cash flow to save or invest for the future, or worse, buried beneath mounds of suffocating debt. In his essay “Bitcoin is Venice,” Allen Farrington states:.

“Those who do not own hard assets are increasingly tending to drown in debt from which they will realistically never escape, unable to save except by speculation, and unable to afford the inflation in the essential costs of living that does not officially exist.”29

Individuals who find themselves in debt up to their eyeballs are certainly at fault, but it’s also important to factor in that debt is artificially inexpensive and money artificially abundant. Seemingly infinite student loans and low single digit mortgages are, at least partially, the downstream result of exorbitant fiscal and monetary incautiousness. Moving away from a system built on debt means there will be, well….less debt. Ready or not, Bitcoin may thrust the 21st century economy into withdrawal, and although the headaches and tremors may be uncomfortable, I believe sobriety from inordinate credit will be a net positive for humanity in the long run. Prominent entrepreneur and tech investor Jeff Booth has described the innovation of Bitcoin as such:

“The technology of Bitcoin allows you to build a system, peer to peer, that doesn’t require debt for velocity of money. And what I just said is probably the most important thing about Bitcoin.”30

I risk being misunderstood here, so allow me to clarify something before I move on. I am not saying debt is inherently bad. Even in a perfectly architected financial system, leverage would, and should, exist. One of my lifelong best friends who is a professional bond trader put this well in one of our personal correspondences:

“Debt has been transformative for the growth of technologies and the betterment of the middle class. Debt allows people with good ideas the ability to create those technologies now, as opposed to waiting for them to have all the money saved up. That connects those that have excess cash with those that need it, so both win.”

What’s said there is in many ways accurate, and the availability of debt and credit has furthered the overall economy and/or led to helpful advancements being pulled forward. Even so, my suggestion is that this has been overdone. An unsound monetary base layer has allowed leverage to expand for too long, in too large a quantity, and in a worrisome variety. (The variety of leverage I’m referring to here was discussed at length in Part 1, namely a substantial amount of credit risk has transferred from the financial system to the balance sheets of nation-states, with the error term in the debt equation being the fiat currency itself.31)

If Bitcoin becomes a reserve asset and underpins even a portion of the global economy (the way gold once did), its decentralized mint and immutable fixed supply could call the bluff on an artificially cheap cost of capital, making borrowing significantly more expensive. It’s important to recognize that BTC is built to be the central bank. Rather than market participants waiting with baited breath to see what color smoke emerges from meetings of appointed Federal Reserve officials, this protocol is constructed to be the arbiter of monetary decision making — monetary physics if you will. Satoshi Nakamoto begged an interesting question for humanity: Do we want a set of monetary rules that a few can alter and everyone else has to play by? Or do we want a set of rules everyone has to play by? In a hyperbitcoinized (and significantly less centralized) monetary future, the levers impacting the cost and quantity of money would be removed (or at least significantly shortened) — the price of money could be restored.

Within a potentially harder digital monetary environment, behavior would be dramatically altered. Inexpensive money changes financial conduct. Artificially suppressed risk free rates trickle through the entire lending landscape, and cheap money enables excess borrowing. To provide a tangible example, consider that a mortgage interest rate of 6% rather than 3% increases monthly payments on a home by 42%. If the cost of capital is accurately priced higher, uproductive leverage will be less prevalent and the detriments of dumb debt will be more visible. People simply won’t be incentivized to “afford” so much stupidity.

Additionally, Bitcoin could (and already is) magnifying the consequences of debt default. When a person takes out a loan, capital is pledged by the borrower to protect the interests of the lender; this is called collateral. The collateral pledged to lenders in today’s financial system is often far from their possession — things like borrower income statements, investment account totals, homes, cars, even cash in the bank. When someone is unable to make payments on a mortgage or loan, it can take months or years before the lender gets restitution, and the borrower can often play “get out of jail free cards” such as foreclosure and bankruptcy. Compare this to Bitcoin, which allows for 24/7 by 365 liquidity in a digital, immediately cash final, global money. When someone takes out a loan and pledges Bitcoin as collateral (meaning the creditor holds the private keys), they can be immediately margin called or liquidated if their end of the bargain isn’t upheld. Responsible creditors in the already existent and exponentially growing Bitcoin borrowing and lending landscape often describe Bitcoin as “pristine collateral,” some reporting close to zero percent loan losses.32 It seems inevitable that more and more lenders will recognize the protections an asset like Bitcoin provides as collateral, and as they do, borrowers will be held to greater account. When loan payments aren’t made or loan-to-value ratios aren’t upheld, restitution can be immediate.

Why is this a good thing someone might ask? I view this as a net-positive because it may help disincentivize unproductive debt. Bitcoin is the ultimate accountability asset — a leverage destroyer and a stupidity eliminator. Financial success is rooted in sound behavior, and borrower habits are bound to improve in a Bitcoin world where incentives are restructured and poor decisions show real and immediate consequences. This will help steer everyday folks away from unproductive debt and lengthen financial time preferences.

From nation states to corporations to the individual, flimsy fiat fiscal and monetary policy has enabled bad habits — bailouts, stimulus, manufactured liquidity, contrived stability, and injudicious capital allocation proliferate without sufficient financial accountability. An applicable analogy commonly used in the Bitcoin space is that of forest fires. When towns and housing developments unwisely spring up over vulnerable landscapes, forest fires are extinguished immediately and substantial burns aren’t permitted. This is akin to today’s economic environment where recessions and lockdowns are quickly drenched with the fiat monetary fire hose. We must heed the warnings of mother nature — uncontrolled fires still inevitably materialize in these vulnerable areas, but now the fire load has built up significantly. Instead of routine burns properly restoring and resetting ecosystems, these rampant infernos get so hot that the topsoil is destroyed and the environment is dramatically harmed. This dynamic echoes what’s occurring in today’s markets as a consequence of artificial intervention. When financial fires start in the 21st century, the magnitude of these events, the efforts needed to thwart them, and their harmful aftermath have all been magnified. If Bitcoin serves as the arbiter of global monetary accountability (as I believe it one day may), our species will learn to better avoid dangerous economic landscapes altogether.

Bitcoin is a new monetary sheriff in town, and although its inflexible rules may be distressing for some, I believe it will contribute to cleaner economic streets and ultimately lead to greater prosperity and egalitarianism. The ability to bail out the individual, the institution, or the system as a whole may diminish, but this pain is well worth the gain as the restitution of sound money in the digital age will drastically improve price signals and create a cleaner playing field. This is destined to benefit the middle and lower classes, as generally speaking, they lack the awareness and/or ability to change the rules of the existing financial game in their favor.

A “Crypto” Caution

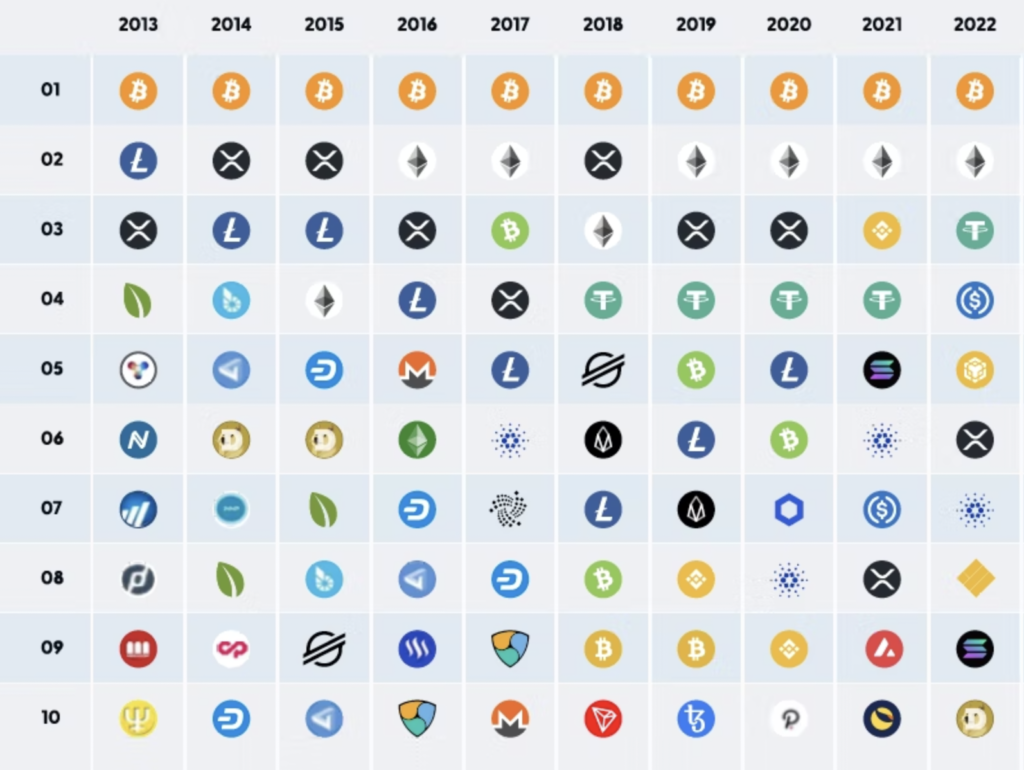

Twenty-first century financial plumbing is certainly dysfunctional, but when we go to replace the leaky pipes, we must ensure we are doing so with well-built, watertight, and durable hardware. Unfortunately, not all the parts in the “crypto hardware store” are created equal. The landscape of cryptocurrencies has grown almost endlessly diverse with thousands of protocols in existence. Despite a relentless cohort of venture capital funds, redditors, and retail investors salivating over the newest altcoins, Bitcoin has proven repeatedly it stands in a league of its own.

Image Source: “Bitcoin vs. Digital Penny Stocks” by Sam Callahan

BTC’s simplistic and sturdy design, unreplicable origin, profound and increasing decentralization, and distinctive game theory have all contributed to an exponentially growing network effect. It seems increasingly unlikely Bitcoin will face substantive competition as a digital reserve asset or store of value. Altcoins come in endless varieties — at their worst they are outright scams; at their best they are attempts to fulfill potential market needs of a more decentralized financial future. In all cases they are far more risky and unproven than Bitcoin. When one makes a decision to buy another cryptocurrency besides BTC, they must come to terms with the fact that they are passing on a protocol that is currently filling an enormous hole in global markets, with what is arguably the largest addressable market in human history.

An exploration of altcoins could be an essay of its own, but in my humble opinion the opportunities I’ve outlined above regarding Bitcoin apply to it specifically, not cryptocurrency generally. At the very least, I encourage new participants to seek to understand Bitcoin’s design and use case first prior to branching off into altcoins. The following excerpt from the piece “Bitcoin First” by Fidelity Digital Assets sums this up nicely.

“Bitcoin’s first technological breakthrough was not as a superior payment technology but as a superior form of money. As a monetary good, bitcoin is unique. Therefore, not only do we believe investors should consider bitcoin first in order to understand digital assets, but that bitcoin should be considered first and separate from all other digital assets that have come after it.”33

Conclusion

If this essay accomplishes nothing else, I hope it motivates the reader to learn. Knowledge is power, but it doesn’t come without work. I implore all readers to do personal investigation. Don’t trust me, verify on your own. I am nothing more than one very limited and evolving perspective. I do believe Bitcoin is a remarkable tool, but it isn’t simple. It can take hundreds of hours of research before its implications click, and thousands before real understanding is reached (a journey I am still very much on). Don’t run before you walk — when it comes to saving and investing, one’s allocation size and understanding should ideally mirror each other.

With the disclaimers complete, I feel all market participants (the middle and lower classes in particular) should consider allocating a portion of their hard earned capital to this protocol. In my view, there is one clearly unwise allocation size when it comes to Bitcoin: zero. BTC is a monetary beast, driven by attributes and game theory that make it unlikely to disappear, and its arrival coincides with an environment that clearly illuminates its use case. It appears the fiat experiment that began in earnest in 1971 is decaying. A tectonic shift is happening in money, and positioning yourself on the right continent may have dramatic implications. Today’s increasingly brittle financial system requires more and more intervention to remain intact. These manipulations have a tendency to benefit incumbent institutions, wealthy individuals, powerful participants, and already severely indebted nation states, while disenfranchising the everyday man and woman. Leaking and corroded pipes are being continuously repaired and jerry-rigged in the economic residence of the middle and lower classes, flooding an already wet basement. Meanwhile, a brand new home with pristine, durable, and water-tight plumbing is being architected next door. The door to this new home is open, and all individuals, particularly average wage earners, should consider moving a portion of their belongings there.

Acknowledgements: Beyond the plethora of people quoted or referenced in this essay, appreciation and credit go to many others for editing and improving this piece — my podcast co-host (and fellow firefighter) Josh, who sharpens my ideas every week and has walked before me every step of the way in my Bitcoin education journey — also Ryan Deedy, Joe Carlasare, DazBea, Seb Bunny, my friend Kyle, my anonymous bond trading buddy, my wife (a spelling and grammar guru), as well as Dave, Ryan, and Jim from the firehouse.

1 The words “credit” and “debt” both pertain to owing money — debt is money owed; credit is the money borrowed that can be spent.

2 The price of money being interest rates

3 For more on how this works, I recommend Nik Bhatia’s book Layered Money.

4 A disclaimer may be in order here. I am not anti-globalization, pro-tariff, or isolationist in my economic viewpoint. Rather, I seek to outline an example of how a monetary system built heavily on top of the sovereign debt of a single nation can lead to imbalances.

5 If you are interested in exploring the nuance and complexity of Quantitative Easing, Lyn Alden’s essay “Banks, QE, and Money-Printing” is my recommended starting point.

6 From “What Exactly Is the ‘Fed Put’, and (When) Can We Expect to See It Again?” by James Lavish, part of his newsletter The Informationist

7 Yes, I admit some of this was the result of stimulus money being invested.

8 From “The Ultimate Guide To Inflation” by Lyn Alden

9 Preston Pysh made this comment during a Twitter Spaces, which is now available via this Bitcoin Magazine Podcast.

10 Although this is often labeled as “money printing,” the actual mechanics behind money creation are complex. If you would like a brief explanation of how this occurs, Ryan Deedy, CFA (an editor of this piece) explained the mechanics succinctly in a correspondence we had: “The Fed is not allowed to buy USTs directly from the government, which is why they have to go through commercial banks/investment banks to carry out the transaction. […] To execute this, the Fed creates reserves (a liability for the Fed, and an asset for commercial banks). The commercial bank then uses those new reserves to buy the USTs from the government. Once purchased, the Treasury’s General Account (TGA) at the Fed increases by the associated amount, and the USTs are transferred to the Fed, which will appear on its balance sheet as an asset.”

11 From “Does the National Debt Matter” by Lyn Alden

12 From “Why Every Fixed Income Investor Needs to Consider Bitcoin as Portfolio Insurance” by Greg Foss

13 When I say “overly monetized,” I’m referring to capital flowing into investments that might otherwise be saved in a store of value or other form of money if a more adequate and accessible solution existed for retaining buying power.

14 Now a book by the same title

15 Said during a macroeconomics panel at Bitcoin 2022 Conference

16 From Lyn Alden’s article “Why Investors Should Care About Interest Rates and the Yield Curve”

17 Source is Parker Lewis’ “The Great Definancialization”

18 For more on proof of reserves, see Nic Carter’s Proof or Reserves page

19 Robert Breedlove does a fantastic job explaining the characteristics of money and how they pertain to gold and Bitcoin in the podcast episode “BTC001: Bitcoin Common Misconceptions w/ Robert Breedlove”

20 For more on this theme, check out “Why Gold and Bitcon are Popular (An Overview of Bearer Assets)” by Lyn Alden

21 If this seems far fetched, remember Bitcoin is open source and programmable like the internet protocol stack itself. Without compromising its core consensus rules, applications and technologies can be built on top of it to meet future monetary and financial needs. This is being done currently on second layers like the lightning network.

22 These aforementioned asset classes are not inherently bad. Investment and lending are key drivers of productivity and growth. However, because today’s money is decaying, saving and investing are becoming synonymous, and even those who want to avoid risk are often forced to take it on.

23 Jim Crider is the first person I heard describe this distinction within the following podcast episode: “BCB029_JIM CRIDER: The Black Sheep of Financial Planning.”

24 From podcast episode “BCB046_Dr. Jeff Ross: Treating Septic Markets”

25 The word “deflation” is controversial, complex, and multifaceted. When I use it here, I am not speaking to a transient or momentary economic event or period; rather, I am using it to describe the potential for inflexible monetary supply in which buying power inherently grows over decades and centuries (think gold and other hard assets). I agree with Jeff Booth that “the free market is deflationary” and that technology inherently allows us to do more with less. In my view, we need a currency that better allows for this. Jeff Booth explores this idea in detail within his book The Price of Tomorrow.

26 From Principles for Navigating a Big Debt Crisis by Ray Dalio

27 From “The European Central Bank Is Trapped. Here’s Why.” by Lyn Alden

28 Extreme indebtedness is not unique to the middle class — all of society is over-leveled from the top to the bottom; however, due to lack of knowledge, education, and access, it’s my contention that the lower classes have a propensity to use debt less advantageously.

29 Allen Farrington now has a book by the same title: Bitcoin is Venice.

30 From Jeff Booth comments at Bitcoin 2022 Conference during a macroeconomics panel

31 Credit goes to Greg Foss for this concept. He explores this in detail within his essay “Why Every Fixed Income Investor Needs to Consider Bitcoin As Portfolio Insurance” (specifically on p. 23).

32 See podcast episode “BCB049_Mauricio & Mario (LEDN): The Future of Financial Services”

33 From “Bitcoin First” by Chris Kuiper and Jack Neureuter