✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🧠 Sound smart? Feed your brain with weekly issues sent directly to your inbox here

Today’s Bullets:

- Foreign Exchange Rates

- How to Read the Quotes

- Impacts to Exchange Rates

- Is the US Dollar Too Big to Fail?

Inspirational Tweet:

Code Blue: Japanese yen.

Cracks in the foundation…

JPYUSD pic.twitter.com/sfCtpAw5J4

— Dr. Jeff Ross (Pleb counselor) (@VailshireCap) April 29, 2022

Dr. Jeff points out the recent troubles of the Japanese Yen here, as quoted against the US Dollar. For an exchange rate to move this much in just a number of weeks, it suggests a structural shift of valuation and a likely underlying problem.

What is the problem?

Let’s dive into exchange rates, how they are priced, and answer exactly that and more below.

📈 Foreign Exchange Rates

In the simplest terms, an exchange rate is the rate at which one currency can be exchanged for another. This sounds rudimentary, I realize, but let’s dig into it a bit.

First, there are different types or regimes of exchange rates: floating, fixed (also known as pegged), or range-fixed, something of a hybrid of the other two. Each country decides their own currency’s regime and structures their treasury actions accordingly.

Floating

With a floating currency, the exchange rate is exactly what it sounds like: free to move in price according to supply and demand for one currency against another in the market. The government does not actively set the exchange rate and allows their currency to fluctuate accordingly. Most currencies in the world are free-floating.

Fixed

In currencies that are fixed or pegged, they choose a currency to peg to, usually the USD, and intervene in markets to ensure the currency remains the same as the pre-determined exchange rate. The only time the rate will change is when the government decides to revalue the currency and thereby reprice the rate of exchange. Most often, this is results in a major devaluing of the currency, as we witnessed most recently in the Venezuelan Bolivar.

The idea of pegging currencies was introduced and adhered to by Western European countries under Bretton Woods at the close of World War II, whereby all those countries would use fixed exchange rates vs. the US Dollar, which was in turn pegged to gold. This system was abandoned in 1971, after Nixon abandoned the gold standard.

Current fixed currency exchange rates include a number of Caribbean currencies, such as the Belize, Bermuda and Cayman Islands dollars, as well as the Saudi and Qatari Riyals and various Middle Eastern currencies, the newly revalued Venezuelan Bolivar, as well as numerous others.

Range-fixed

Finally, some governments aim to keep their currency valued within a narrow range against another currency, in particular. This, in turn, will keep it in lock-step with that currency versus other currencies around the world, but in a tight range.

A prime example of a range-fixed exchange rate would be the Hong Kong Dollar (HKD) vs the USD. While the HKD has gone through a number of iterations of fixed and flexible pegging to the USD over the years, it now is pegged to a range of 7.75 to 7.85 HKD to USD now.

OK, now we’re clear on the types, what about the system for quoting the prices of them?

🧐 How to Read the Quotes

As you may have noticed, some exchange rates are quoted differently—with one being dominant over the other, depending on the currencies being priced and the generally accepted market quoting convention. According to where a price is being quoted, one currency will always be dominant over the other.

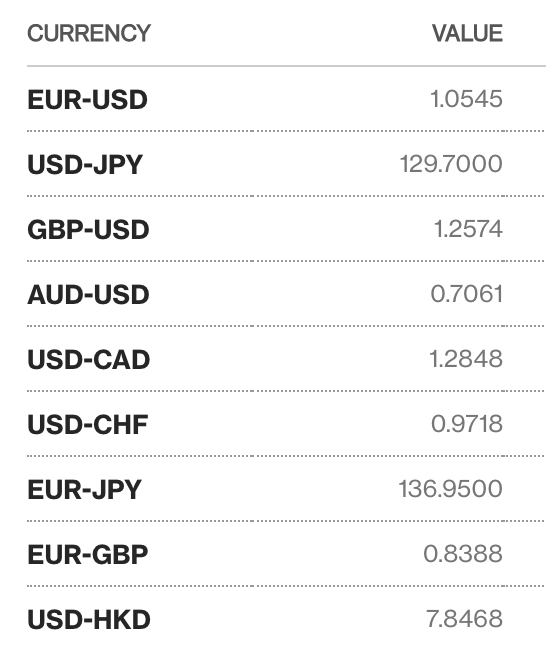

For instance, as you can see here, when markets quote the USD versus the EUR, they show how many USD you can get for 1 EUR, or 1.0545 today. This is the same for the GBP.

*https://www.bloomberg.com/markets/currencies

However, when pricing the USD to CAD, the quote will normally show how many CAD you can get for 1 USD, e.g., 1.26 CAD. You can see the convention is the same for the Japanese Yen (JPY) and Australian Dollar (AUD).

It’s confusing and frustrating for sure, especially to non-forex (Foreign Exchange) specialists. I remember when I first joined SG Warburg, a UK-based trading firm on Wall Street, and was immediately being trained to trade arbitrage between foreign and domestically traded shares of companies. One of the key inputs for determining whether or not to execute a trade was the foreign exchange rate between the countries.

Get that part wrong and it could cost your bank big money and you your job. Absolutely maddening until the quoting conventions became second nature to me. The good news is that most retail trading platforms make it explicitly clear what is being priced and how, these days, helping eliminate the opaqueness of institutional trading conventions.

So, now we know how to read the quotes, but what exactly impacts the exchange rate of these quotes? What makes one currency stronger than another?

💥 Impacts to Exchange Rates

There are numerous factors that affect the value and pricing of one currency to another. And if you’ve been following what’s going on in the world lately with inflation, interest rates, and bond purchases/sales by central banks, then you’re already in tune to some of the forces impacting the price of currencies. That said, let’s walk through a few of the major ones here.

First and foremost, the general and perceived economic strength of a country is important to its currency. This encourages people, companies, and countries to hold certain currencies and not sell when they have some in their personal bank, company treasury, or central bank reserves.

That said, two major factors will impact and either increase or decrease the real and perceived economic strength of a country: trade balances and interest rates.

For good reason, a major force of currency valuation has to do with a country’s trade balance. When a country is a net importer (meaning that the country imports more goods than it exports), this means that net-net, people and companies are exchanging (selling) the local currency to receive (buy) foreign currencies needed to purchase those excess goods. This puts downward pressure on the local currency as it is being sold in the foreign exchange markets.

And when a country is a net exporter (the country exports more goods than it imports), the opposite is true. Demand for the local currency is higher as foreigners must buy that currency and sell their own in order to buy the other country’s goods and services.

Next, when a country has high interest rates in relation to other countries, this increases demand for securities and financial instruments based in that country’s currency in order to take advantage of these attractive rates. Put simply, when you purchase a country’s bonds, you must pay for them in that country’s currency. If you want to buy US Treasuries, you must convert your home currency to USDs to buy them, and if you want German Bundesbonds, you need to convert your currency to EUR to pay for them.

Bottom line, when one country’s interest rates are rising head of other countries, it will create demand for that country’s bonds and, in turn, that country’s currency.

Then what about inflation, you may ask.

Put simply, as you have likely seen, inflation can have a major negative impact to a country’s currency. Because as a country suffers from inflation, i.e., it takes more currency to buy goods and services in that country, the currency depreciates against other currencies. In extremes, we see hyperinflation, and without a formal revaluation (devaluation), this will cause a currency to collapse. We have most recently seen this in major countries like Venezuela, Lebanon, and Turkey, as well as others.

And as we see in Dr. Jeff’s post above, it is beginning to negatively impact the Japanese yen these last few months. The main reason: The Bank of Japan recently announced a yield curve control program to buy an unlimited number of Japanese 10-Year Treasuries in order to hold the yield at .25%. The excess printing by the Bank of Japan (in order to buy all these Treasuries), coupled with the pressure of foreigners selling Yen when selling those treasuries, has had a major negative impact to the Yen exchange rate.

Other factors that are closely related to the factors listed above include central bank fiscal policy and monetary and currency manipulation. Excess printing of a currency devalues it against other currencies that are not being devalued at a similar rate. Excess debt versus GDP of a country can impact the credit rating and perceived strength and safety of a country’s debt and currency.

Furthermore, a country actively and aggressively manipulating its own currency in the open markets can impact the balance of trade and their levels of imports and exports versus other countries.

Looking at all this and thinking through the factors above, it may be obvious to ask why the USD continues to be so strong in the face of all the local negative developments lately. There are a few structural factors that we can point to, such as the USD being the reserve currency of the world, primarily because virtually every country uses USD to buy and sell oil and gas globally. All this strength and confidence has led to many countries holding US Treasuries as a reserve asset on their balance sheets. And so, in effect, they own US Dollars.

Question is: Is the US Dollar too big to fail?

💵 Is the US Dollar Too Big to Fail?

The short answer to that question is no.

In fact, if history is a reliable guide, every single fiat currency (one issued and backed only by the good faith of that country) in the history of the world has failed.

Without going too deep into it, the simple answer of why they fail is: inflation and/or eventual loss of confidence in the issuing country. And because we mathematically need inflation to cover and pay off the enormous debt load of the United States, the country’s balance sheet will eventually collapse under the weight of it.

Unless, of course, the US decides to act swiftly and begin adding a different reserve asset to its balance sheet in order to back the USD effectively.

Exactly. With Bitcoin.

The purest and hardest form of money ever created. It is the only asset in the world that will not devalue over the future, as it has a finite supply that can never change.

And if the US Government ignores the reality of the problem, does not act to buy, mine, and hold Bitcoin on its Treasury balance sheet as a reserve asset to back the USD? If the US continues to use US Treasuries as its own reserve asset?

The USD will eventually fail. Period.

When this happens, and how quickly once it starts, is anyone’s guess. It could take many more years or decades from here. Even if it is the last fiat to fall, it will eventually. It’s mathematically impossible to avoid.

But you can still protect yourself from this gross ignorance and negligence.

You may have heard me talk about it before, but I believe Bitcoin is the strongest and safest insurance against a total and catastrophic collapse of global fiats. To read more and dig in a little deeper on that, I wrote a whole thread for you. If you have yet to read it or need a refresher, here it is:

As a risk trader, I’m always concerned about 'Tail Risks'.

And #Bitcoin hedges against the biggest tail risk we’ve ever faced in the history of the modern financial world:

An all out collapse of fiat currencies.

How? Let’s break it down nice and easy here 👇🧵

— James Lavish (@jameslavish) February 15, 2022

That’s it. I hope you feel a little bit smarter knowing about currencies, foreign exchange and the reality of the USD and other fiats.

As always, feel free to respond to this newsletter with questions or future topics of interest!

✌️Talk soon,

James

Few people really realize that the US dollar is only, at least in how one should think about it, about 50 years old. I have no affiliation with the site, but wtfhappenedin1971.com is a great place to see visualizations of the this current dollar regime. Could the dollar fail? Sure. But (aside from Bitcoin) it’s still the cleanest shirt in the dirty laundry hamper. In my opinion, US dollar appreciation is still more likely in the short-mid term (Brent Johnson’s Dollar Milkshake Theory)… James, do you see dollar inflation or deflation as a bigger risk in the next 5-10 years?