In one of my previous articles, I spoke about inflation and explained how inflation is eroding our purchasing power. Over time our dollars lose their value and buy us less and less stuff. If you would like a recap on that, please click here.

In that article, I raised concerns about how interest rates are not playing the role of the protector against inflation as they once did. Without decent levels of interest rates, once we factor in inflation, our currency goes backwards in real terms. We often hear things like “The Reserve Bank is holding the cash rate at 0.5%”, but what does that actually mean? When they say cash-rate, is that the same thing as interest rate, treasury rates or real yields? It is easy to see why Average Joe throws his hand-ups up the air in confusion. Really, for most people I know, middle-income workers, all we care about is what our home loan rates are, but the rabbit hole is deeper than most of us realise.

I am actually not really here to talk about mortgage interest rates today, although I will touch on them briefly to illustrate some of the differences between the terms highlighted above, I am more interested in giving you some insight into treasury rates and why they matter. We need to get a good understanding of bonds. Bonds play an integral role in global finance, specifically, US treasury bonds and their associated US treasury rates. A lot of the key terminology and takeaways from this article are equally transferable to other treasury bonds such as those from sovereign nations with sovereign currencies like Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the UK. We will look at this key terminology in detail, breakdown yields and look at how the FED controls yields with Quantitative Easing.

I will demonstrate in this article why global debt has us cornered and why interest rates are the biggest threat to popping this massive debt bubble. We will look at why the FED and central banks (incl the Reserve Bank of Australia) are hell-bent on keeping the system afloat. Throughout, I hope to highlight how these policies are making the rich wealthier all the while hollowing out the middle class.

US Treasury Bond

Breaking down the terminology

Let’s get some terminology out of the way.

Bonds. The easiest way of understanding a bond is to think of it as a loan. When governments or corporations want to borrow money, they (usually) don’t go to a bank like you and me, they go to the bond market. They issue bonds, on the promise to pay back the principal (the amount borrowed) at the time of maturity (at the end of the stipulated term) and they will pay a coupon (interest rate) at predetermined intervals.

When a government issues a bond, they call it a treasury bond. Treasury rates are therefore the coupon/interest rate that the government must pay to the holder of the bond. These treasury rates are the cost of capital for the government. In a normal, free and open market, the government’s treasury rates would be determined by the supply/demand equilibrium we have discussed in other articles. Meaning, if the particular government in question was a risky borrower (like us, governments have credit ratings too), the markets appetite to buy these bonds may be low, meaning nobody wants to buy these bonds, and the government in question would have to raise the coupon on offer to entice people to buy them. In a free and open market, this level would soon be found as lenders find the rate they would require for taking on the risk. If you didn’t quite follow that, fear not, we will revisit it soon to hopefully make the concept a little more palatable.

Cash-Rate. There is a difference between the treasury rate as we defined above and the cash-rate we sometimes hear on the news. When we hear: “The Reserve Bank says they are holding rates at 0.5%”. What they are referring to is the cash-rate. This is not to be confused with the treasury rate. The cash-rate is the rate at which banks borrow money, either between themselves or from the Reserve Bank. This is the base-layer cost-of-capital for banks and is the base rate for what sets the interest rate on your homes and the interest rates you earn from your deposits in the bank.

Interest rates in and of themselves are a general term describing the concept of having a cost of capital. In other words, how much does it cost me to borrow? Interest rates themselves require more context when talking about them, they can equally be talking about cash-rates, treasury rates, corporate bond rates, fixed-term deposit rates, home loan rates etc etc etc.

Corporate Bonds. As we saw with treasury bonds, corporations can also issue bonds called corporate bonds. When corporations want to grow or expand they can go to a bank like you and me and pay the bank interest, or they can issue bonds on their own terms and let the market decide. They work very similarly to a treasury bond.

Let’s look at an example so we can identify a few more pertinent terms.

E.G Dazza’s Antique Guitar Store Pty Ltd issues a series of $10,000 bonds, with a 6.5% coupon paid quarterly and with a maturity of 10years. This means they borrow $10,000 on each bond they issue, they pay 6.5%/year interest which is paid every 3months, and at the end of the 10year term, they pay the holder of that bond the original $10,000. On issuance, this bond has a 3% yield.

Key terms we can identify from the above example:

- Principal/Face Value/Par Value — the amount that will be paid at maturity ($10,000)

- Coupon Rate — the amount of interest paid (6.5% annually)

- Coupon Dates — When the coupon interest will be paid, semi-annually or annually are common (quarterly in the above example)

- The Maturity Date — The date at which the face value will be paid to the holder (10 years from the date of issuance in this example).

- Yield — The return we receive from ownership as a measure of the expected return vs price paid. We will visit this in detail later.

Mum! Where do bonds come from?

When a government of corporate bond is issued the bonds are normally traded on the primary market (e.g investment banks etc). Investment banks and primary dealers attend these primary bond market auctions (sorry, no average Joe’s allowed) and they get first crack at the loot. Once purchased they can be held until maturity of the bond where the holder simply collects the coupon. Or, these dealers sell the bonds on the secondary market between other banks, institutions, funds and retail investors. The secondary market is where bond prices come into play and where we need to start thinking about yields. I’ll get to yields soon I promise.

Where do treasury bonds come from?

As we highlighted earlier, treasury bonds are government-issued debt. They issue debt so they can spend it. When they spend more than they make from tax revenue, they call it a budget deficit, but that money has to come from somewhere. Let’s look at our favourite monetary degenerate the US of A. When the US government wants to spend currency they go and look in the cookie jar and (more often than not) realise it is empty. They then go to the bond market to borrow some. Uncle Sam is “always good for it” so there is (usually) demand for their debt. Meaning there is usually a long list of banks and nations waiting to lend the US government currency. Why? Because they will never default on their debt, they can always print more, so it is considered a safe haven for investments. Please read my article on Fiat Currency for an understanding of how the US is able to print as much as they like (and do print as much as they like, this is key to getting a holistic view on finance).

I just mentioned that there is “usually” demand, outside of the fact they won’t default, but where else is this demand-driven from? The US runs massive deficits through imports (this means they import more goods than they export). This effectively means they export lots of USD to other countries. Other countries such as China, for example, have little use for USD inside their own country because they have their own fiat currency. This means China either sits on big piles of worthless USD they can’t use, or they can invest them back into the US by buying US Treasury Bonds which they receive a coupon for their trouble. (At least this was the case, China now invests USD in foreign infrastructure projects and has very low US treasury purchases in 2021, but they were once one of the biggest purchases of US debt). Because of these USD exports, there is usually high demand for US treasuries as countries lend back their USD in exchange for the coupon. This demand for US debt is what helps to suppress interest rates. To elaborate, if we look at this in simple supply/demand economics terms, if there is demand for US debt, the US does not have to try and entice anyone with attractive interest rates on their coupon. If that situation were to reverse, and the demand for US debt was to taper, the US would have to raise interest rates to make this debt more attractive to lenders.

A debt problem and an interest rate problem in one

The world is in a massive debt bubble. The US is undoubtedly in a bad way, but not many nations aren’t. The US debt total at the time of writing in June of 2021 is ~$28.42 Trillion USD (see Figure 1). That is a phenomenally large number. We throw “trillion-dollar spending” around like it means nothing these days. The number “one-trillion” is almost too large a number for the human brain to comprehend. If you wanted to count to one trillion, counting up by 1 digit per second, you would have had to start counting around 29,000BC. If you were able to earn $1Million per day, it would take you 2739years to save $1Trillion Dollars (don’t try and work it out with your own wage, it will only depress you). The point to me highlighting this is to highlight the fact that the US simply cannot afford for interest rates to go too high from current levels. The higher interest rates go, the higher the servicing costs of their massive debt pile would become. This would have an even bigger crippling effect on their already gigantic debt issue.

Figure 1. The US Debt Clock https://www.usdebtclock.org/

But on the flip side of the high-interest rate argument, what happens when interest rates get so low that demand starts to taper off? Meaning, what if the coupon the US pays for its debt becomes so low that lenders no longer see value in holding the bonds. When lenders are no longer interested in 1% interest rates, they start looking for alternative investments (e.g look at China and their Belt and Road initiative). But if the demand is gone, the US is forced to raise interest rates to attract lenders right? But we just saw that the US can’t afford for interest rates to get too high because the cost of servicing their debt will cripple them even further into debt. They are already in a hole they can’t get out of.

To reiterate, if demand for US treasury bonds starts to wane, this puts a strain on interest rates. Higher interest rates don’t just stress the government and their ability to service debt, it puts pressure on the interest rates of everything and this can have major implications on markets and the economy as a whole.

The US Treasury rate is considered the Risk-Free-Rate-of-Return. Why is it considered risk-free? Because as I highlighted earlier, the US will never default on their debt (theoretically). They operate a fiat currency that isn’t backed by anything. We have been on a fiat currency standard since the 70’s. They can and will just print more money when the maturity of their bonds draws close. In 2021, they don’t even actually “print” it anymore, they just add a few more 0’s on their accounting system. Simple. So because they will never default on their debt (in real terms at least, inflation is a whole other side of this argument, but for now……), their debt is considered risk-free.

Because the US treasury is considered the risk-free-rate-of-return, it becomes the yardstick by which pretty much every other financial instrument is measured. To elaborate, when corporations issue their bonds, they are forced to compete with the government for capital (compete for the capital of lenders). But corporations are not considered risk-free like a government that has a license to print currency. Corporations that mismanage their finances do often become insolvent. These corporations get liquidated, meaning anything that can be sold off is sold off to pay off debtors and creditors. Lucky for bondholders, they are one of the first in line to be paid (before shareholders at least). But as is often the case, a failing business doesn’t always have enough assets to liquidate at par value (meaning bondholders are left short). Therefore, if you are to lend to a corporation instead of the US treasury, you are taking on a risk and you will want to be rewarded for this excess risk you are taking. It is not then unreasonable that you demand a higher coupon rate than that of the US treasury bond. It would be very rare indeed to see newly issued corporate bonds with coupons lower than the treasury rate and even rarer to find a buyer of that debt.

Corporate debt — it’s no better

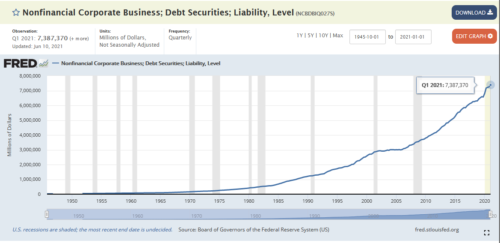

We are starting to now build a picture of how all these puzzle pieces fit together and why interest rates are a problem. Just like the US debt levels, corporate debt levels are also higher than they have ever been in history. Figure 2 shows the increase in non-financial corporate debt levels for the US to date. That’s just about $7.4Trillion.

Figure 2. Corporate Debt Levels: Source: St Louis FED.

This massive wall of debt is confronting, what is more confronting is that a large percentage of this debt is due to mature in the coming years. This means, if treasury rates are allowed to spike, corporations will have to compete with higher coupon rates to attract the attention of lenders. Earnings have fallen short for many corporations under straining economic conditions in recent years, making it harder for corporations to simply pay off these maturities from their retained earnings/profits when the debt falls due. This forces those corporations to reissue the debt again to pay off these maturing liabilities, effectively swapping old debt for new. Higher interest rates would mean higher coupon payments, which will then eat further into these declining earnings we just highlighted. It is now a vicious cycle and explains exactly how and why we are in the place we are in globally. That is, massive debt piles and governments forced to keep interest rates low to keep the system afloat.

Revisiting Inflation

Let’s throw another spanner into the works. Inflation. Inflation is the increase in the cost of goods and services and the decrease of the dollars purchasing power. For a deep dive on inflation, click here for one of my previous articles. When we throw inflation into the mix we put upward pressure on interest rates through lender demand. As inflation rears its ugly head, lenders demand higher interest rates to try and counteract the inflation they see in goods and services. Interest rates are the main protector when it comes to inflation. So if interest rates are currently low, but inflation is high we start to lose the “demand” side for new issuance and lending. If inflation is present and is of significant levels (which it is at the time of writing) then interest rates levels that are lower than the rate of inflation basically ensure that you lose money in the long run in terms of purchasing power.

Yields

So we are starting to see now that it is a complicated balance between risk, rates of return, inflation expectations and supply/demand that dictate treasury rates. Let us now introduce a few more terms (stick with me, this will all come together I promise). Let’s now look at the terms “yields” and “yield-curve”.

I spoke briefly about the secondary market a little earlier. The secondary market is where the majority of the trading of bonds occurs. What ends up happening in free markets is that interest rates are determined by the market based on the demand for the debt. If you are a high-risk borrower, expect to have to pay a higher interest rate. It is pretty simple. But now let’s look at how the secondary bond market works and now how bond prices come into play. “Wait, you said before that a $10,000 bond is purchased for $10,000, and then you get a coupon, and you get $10,000 back at the maturity date, that’s pretty straightforward”. This seems like all there is to it, but what we have is a secondary market where these things get traded. And where there is a market, with supply and demand forces, you naturally get price discovery between people wanting to sell and people wanting to buy. People sell bonds all the time, they might be traders, they might be sold to cover debt obligations or margin calls, they might want to buy a house, retirees sell bonds for currency to live off etc etc etc. And likewise, people are looking to buy all the time for many reasons and financial goals.

But, as we know, interest rates change from time to time. So what happens if I own a $10k treasury bond paying a 1% coupon with 9 years remaining until maturity but interest rates for some out-of-this-world-reason are now 5%. Who would want to pay $10,0000 for something that will give them 1%, holding that for 9 years when they could go straight to the market at get the same thing paying a 5% yield? Nobody that’s who. But what if I really need the money? Well, I go to the market, and I see what I can get for it.

Here’s an example so we can dive into some figures to paint the full picture.

Say the current treasury rate is set at 2%, we could expect the high-grade corporate bond issuance then to be somewhere above that 2% mark, let us say 3%. (I haven’t spoken about high-grade yet and what that means, suffice to say it means the least risky borrowers from the corporates, that’s if you believe the credit rating agencies. Go watch the movie “The Big Short”).

Back to the example. Say I hold a $10,000, 10year high-grade corporate bond with a 3% coupon, theoretically, that bond is worth $13,000 including the par value and the total returns it will pay. I.E the $10,000 par value, and $300/year in interest payments x 10years. Therefore:

$10,000 + $3000 = $13,000.

Now If I wanted to sell that bond, should I expect to be paid the full $13,000 for that bond?

Probably not because the buyer wouldn’t be making anything from it in real terms, and after all, I only paid $10000 for it in the first place. If I bought it new today and sold it tomorrow, if things remained unchanged in the market (i.e interest rates remained the same) I could probably expect to be able to sell it again for $10,000. But free markets are free markets and the bid and ask for all financial instruments find an equilibrium between supply and demand. Theoretically that bond could trade for any amount from zero to infinity if there were someone willing to buy at any price and someone willing to sell at any price. But again that equilibrium is always found and a realistic water-mark would be found for that trade to occur.

Now say I only bought this bond a few weeks ago, but something changed in the economy and the Fed decides to hold down treasury rates from 2% to 1% to try and stimulate spending and growth. Newly issued High-Grade Corporate bonds are now trading at 2%. Now my 3% yielding bond starts looking pretty attractive to other investors. If I were to go to the market now to offer my bond, I could expect a premium above the $10,000 I paid for it purely based on the fact that you can only get 2% coupons from the new issuances.

If we compare the 3% yielding bond to the 2% yielding bond over the maturity of each we can see that the 3% bond will return $13,000 over the 10years compared to $12000 from the new issuance at 2%. That is a whole 10% more over the lifetime of the bond. I could realistically expect someone to pay me anywhere from $10,000 up to a realistic buffer under the difference in the offering (i.e $11,000) when compared to the 2% yielding bond.

Let us now look at real rates or real yield. Real yield means, what am I really getting back in terms of return for my investment if I pay a premium or discount to the par value of a bond. In this previous example above, say someone purchased my 3% yielding bond for a price of $10,500, we can now work out what the Real Yield is for the new holder of the bond. We would expect that the real yield will be lower than the coupon rate because that person paid a premium of $500 for my bond above the par value. They essentially paid $500 for the privilege of earning the 3% coupon. Unlike when I bought the bond for $10k to earn a total of $13k for the life of the bond, they paid $10.5k to earn $13k. They are not making 3% for a $3000 profit for the life of the bond, but rather they are only getting $2500 for the life of the bond. Their yield can therefore be calculated with $2500/$10500/10years = 2.38%/year. The 2.38% is known as the real rate or simply the yield because even though the coupon still says 3%, the premium that was paid has now reduced the total return of profit and thus has changed the real-rate-of-return.

While it is rare to have large interest rate changes by a whole percent as we demonstrated above, the example above is indeed a realistic example of how bond prices are sought in the secondary market This explains why we have a secondary market as investors and traders constantly look for ways to earn a return.

The same math obviously works for the reverse situation. A situation where we had an increase in the treasury yields for new issuance may result in me having to sell my bond for less than the par value. If interest rates were higher now then I would expect to be paid less than $10,000 for my 3% bond if investors could get 4% in the market. The market would find an equilibrium balance for the change in rate in terms of the real rate of return.

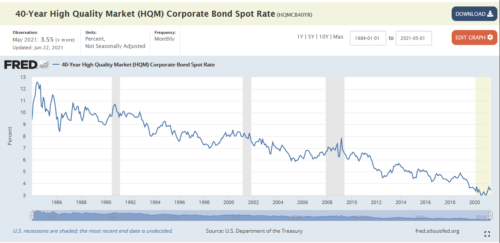

The trading of bonds is where a lot of investors make their money. They make their bets based on where they think interest rates will move in the future. If you think rates will continue to go lower, then buying bonds you know you will be able to sell at a premium later is a great way to skim off the top. This has been the case for over 40years, lower yields have meant that the high end of town, the guys that play in these markets have made an absolute killing, we have had 40 years of steady corporate interest rate declines. (Figure 3). I don’t suggest the Average Joe try this, this is not a game for new kids, this exercise was purely illustrative of the mechanics behind yields which was needed to form the basis for the next part of the article.

Figure 3. 40years High Yield Bonds — source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/HQMCB40YR

FED Controlled Yield — Quantitative Easing

I have mentioned in my examples above the scenario of the FED cutting interest rates, and we highlighted the difference between the cash-rate (the rate at which banks borrow currency) and the treasury-rate (the rate at which the government borrows money). So what does it mean when you hear that “the FED is controlling rates” or when finance news outlets talk about “Yield Curve Control”? Perhaps you have heard of the term “Quantitative Easing”. When the Fed talks about controlling rates through Quantitative Easing (QE) they are specifically talking about controlling the yields on the treasury rates.

Put simply, Quantitative Easing means, we will print currency out of thin air and buy as many bonds as we need to from the primary dealers in order to control yields. Remember our definition of yields above? Go back and read through again if you haven’t quite got the concept down just yet, it’s important to understand.

We can look at March 2020 to illustrate how and why QE was implemented. When the world started to realise that the global pandemic threat was real and lockdowns started to get imposed, it shook the markets. When people panic in markets they try to flee to the most liquid asset there is, the US Dollar. As more people panic, the markets become a violent feedback mechanism, falling asset prices spook more people, more people sell which puts more pressure on prices to the downside, which panics more people again, and down….. we……. go……

As asset prices start to plummet, those who take out leverage (those who borrow currency) to purchase assets get margin-called. This subject needs an article all on its own, but suffice to say that as the ratio (margin)between collateral (the assets they stake) to loan amount gets squeezed, the lenders of the leverage demand more collateral to back up their positions. People who take this leverage have 2 choices:

- They sell other liquid assets (e.g other stocks/bonds) to get cash to cover their margin-calls.

- They close out their positions. Another term for this is they are liquidated and depending on the brokerage system used, this can often be done automatically if the Loan-To-Value ratio is exceeded. To elaborate, the price sell-off can happen so quickly, people don’t even have the opportunity to react and stake more collateral, their position is simply closed out automatically.

Both of the above scenarios put even more downside pressure on asset prices and this feedback loop is multiplied. This explains why when we see market turmoil and asset sell-offs, they can be violently quick to the downside.

In March 2020, we experienced just this, a violent sell-off in equity prices. Historically, if there existed stock market volatility, people would flood to bonds as their safe haven asset. Stocks and bonds would often see-saw if one or the other were in trouble, the other would see a spike in demand. But in March 2020, we saw both asset classes sell-off. This is a worst-case scenario for the government and the FED.

The sell-off in treasury bonds in particular was of major concern. As we highlighted above when we looked at yields, a decrease in demand for treasury bonds, leads to a discount to the principal value of that bond which naturally leads to an increase in the realised yield. To elaborate, when the market panicked, people were desperately trying to sell off their bonds so the supply of bonds went through the roof. But there was little to no demand, nobody wanted to buy these bonds. So the “bid” (the price buyers are willing to pay) went lower and lower and the “ask” (the price sellers are willing to sell for) had to chase them down. The spread between the discount paid to the par value grew, resulting in a high realised yield. As we already highlighted this is a major problem when we are entering a period of economic uncertainty (e.g a global pandemic) because governments want to spend during these times. To spend means they need to borrow. To borrow means they need to issue more bonds, which in turn means they need to compete with these realised yields being achieved in the secondary market.

To prevent the stock and bond markets from spewing any further the FED come out and announce that they are starting Quantitative Easing (again). How QE works is the FED print currency (by adding some new 0’s to their balance sheet and to the reserves held at the banks) and they swap these digitally printed dollars for the bonds (at any price) to control the yields to within what they deem to be an acceptable level. This is known as providing liquidity to the market by signalling to sellers that there will be a buyer if they wish to sell. They started this current round of QE in March 2020 and they haven’t stopped. Australia is no different and we even go as far as announcing yield-curve control where they specifically announce an interest rate target to maintain with their freshly printed currency. The FED/RESERVE BANK/

I go into this concept of money printing further in my article on Fiat Currency, I highly suggest you read it if you haven’t already. This article will provide you with a good understanding of the Cantillon effect and how QE makes the rich more wealthy while making the lower/middle class poorer.

To recap, the FED steps in by printing money to prevent systemic collapse. We have created huge debt bubbles, but this problem is never resolved, we simply keep kicking the can down the road for future generations to deal with. We need to bleed it out now and a fiat currency system is keeping a band-aid on it while robbing the middle/class.

Conclusion

In a free-and-open market, corporations who mismanage debt and finances are liquidated and sold off, and the new generation of emerging entrepreneurs get to have a crack. This is capitalism. Instead of a free-and-open market, we have lobbying and perverse incentives structures designed to maintain the status quo. Politicians are only concerned with their next election cycle and do not and will not make the hard decisions. There is no doubt that there would be significant pain in the interim if they allowed this to happen, but at least we would see it coming. They hide behind the hidden taxation we experience through inflation that makes us poorer as a result of their policies. The bifurcation that exists between the wealthy and lower classes is exacerbated. But those closest to the injection point of the fiat currency become wealthier and have no incentive to change the system.

Do we allow short-term austerity and pain in order to allow the system to correct itself as it should? Or do we keep intervening with the only way we know how? By printing more money.

Moving to a hard money standard is the only solution. When corporations mess up they SHOULD be liquidated, not bailed out. We the taxpayers front the bill, either directly through taxation or indirectly through inflation, but don’t be naive about who is paying, it is us. The richer you are the less you feel it, in fact, you benefit from it. The system is broken and needs to be fixed. A hard money standard is the only solution.

But what can you do? Educate yourself, speak up and be heard. It is one of the driving factors as to why I am writing these articles. Talk to your friends and family and educate them about what is going on, it is the only way we will drive change.

What can you do for yourself in the interim? You can protect yourself. Implement a hard money standard for yourself and for your family by stacking hard money. Take the option off the table for them to debase your $$$ away from them. Start opting out of the system. Governments and Central Banks can’t print hard money. If you hold hard money like bitcoin, it goes up in value over time and it cannot be debased by excessive central bank printing, in fact, bitcoin benefits from excessive printing as the value goes up in purchasing power over time when compared to that currency.

Adopt a dollar-cost-averaging strategy to iron out the volatility (it is still volatile). I know I have covered this in previous articles but it is a very important point. Refer to my article on Inflation vs Savings this article and scroll to the end for information on deploying a dollar-cost-averaging strategy to ensure you are benefiting from this volatility.

If we all start moving to a hard money standard we can change the system from the inside. If we hold money that goes up in value we can level the playing field, we are still early in the bitcoin journey. If we compare crypto adoption to the adoption of the internet we are in the year 1997. Exponential growth is happening but we are still very early. I hear people say but bitcoin is $35k, I have missed the boat. No you haven’t you can buy 0.00000001 bitcoin if that is all you can afford, the important thing is you just need to start moving excess fiat currency out of your bank and into bitcoin.

I will leave it there for this week. I wanted to desperately include how depressed Treasury yields help to artificially inflate other assets such as equities, but this article was longer than I anticipated. Until next time, happy stacking.

Daz Bea

Even among the financially literate, bonds are incredibly misunderstood. When you think that many (most?) people contributing to a pension have a 60/40 split, the lack of bond education is borderline criminal.