✌️ Welcome to the latest issue of The Informationist, the newsletter that makes you smarter in just a few minutes each week.

🙌 The Informationist takes one current event or complicated concept and simplifies it for you in bullet points and easy to understand text.

🧠 Sound smart? Feed your brain with weekly issues sent directly to your inbox here

Today’s Bullets:

- Types of defaults

- History of defaults

- What happens in a default?

- Who’s most in danger to be next?

Inspirational Tweet:

Sri Lanka stopped paying foreign bondholders this year. Russia followed in June. Next sovereign-default candidates include Pakistan, Ghana, Egypt and Tunisia.

— Bryan Solstin (@BryanBSolstin) August 10, 2022

Tell the truth, are you surprised that all those countries could default on their debt in the coming months? Sadly, it’s not all that uncommon. But the question is, what actually happens when a sovereign defaults on their debt?

Grab a cup of joe and let’s walk through it, shall we?

🤕 Types of default

Let’s first talk about the structure of sovereign (country) debt, and how it’s different from bonds issued by a company.

As you may know, the largest market difference between the two is that sovereign debt is far more liquid and often considered much safer than corporate debt. Put simply, trading a hundred million dollars worth of Treasuries is typically as easy a quick phone call with settlement instructions.

Try that with Tesla bonds.

As far as structural difference, corporate bonds are either backed explicitly by specific assets or implicitly by claims on remaining assets of the company. This backing reduces the risk to the creditor (the buyer of the bonds). In contrast, governments issue their so-called risk-free debt with absolutely no explicit or implicit backing at all.

Countries basically rely on their future power to tax as a promise to repay their debt. And they can do this even as they operate (as many emerging and developed countries do) in perpetual deficits. And so, when continued borrowing becomes difficult, when they are unable to pay for the debt they’ve already issued, they can default. And there’s pretty much no recourse for creditors but to accept terms offered by that country for restructuring that debt for partial repayment.

Think about it. If Ghana defaults on its debt, and the California Pension Fund (CalPERS) owns some of that debt, what can CalPERS do? They can’t sue Ghana in American courts, they can’t legally take possession of land or local assets of Ghana. The only recourse they have is to join other creditors in restructuring talks to help shape an agreement that gets them paid as close to par as possible.

This is far different than if CALPERs owns BBBY (Bed Bath & Beyond) debt that’s to be settled in a well-developed and defined US bankruptcy court system.

So, what exactly is a default, then?

From a legal standpoint, a default is a breach of the debt contract. This is typically the failure to pay scheduled debt service (the coupon payment) on time, or within a specified grace period.

From here, it becomes a bit of an academic debate. The IMF likes to distinguish between pre-emptive debt restructurings (debt terms renegotiated before a payment is missed) and post-default restructurings (terms of settlement decided after payments are missed).

Investors, on the other hand, along with credit-ratings agencies, consider a default to be any situation where a sovereign offers restructuring terms that are worth less than the original debt.

So, how exactly does a default happen in the first place?

I mean, modern monetary policy allows countries to continue to operate in growing deficits and just issue more debt to pay for those deficits and, hence, the interest on past debt.

True, but this can only go on for so long, especially for emerging and developing economies, as well as some advanced countries that are finding themselves in crisis recently.

And with all this debt piled upon debt, there are a number of events that could negatively impact a country’s ability to either borrow more and/or keep up with payments on debt that they already owe.

Economic downturns, periods of trade shocks, and, of course, the devaluation of a local currency can all wreak havoc on a sovereign’s liquidity.

I’ve recently spoken about the problems of over-indebted sovereigns, and we’ve talked about the troubling position that even the US currently finds itself. If you haven’t yet read about that, I wrote a whole Informationist Newsletter on it.

You can find it here.

But in summary:

increased cost of borrowing → debt grows faster than expected → external demand for debt decreases → interest rates increase more → debt spiral → default

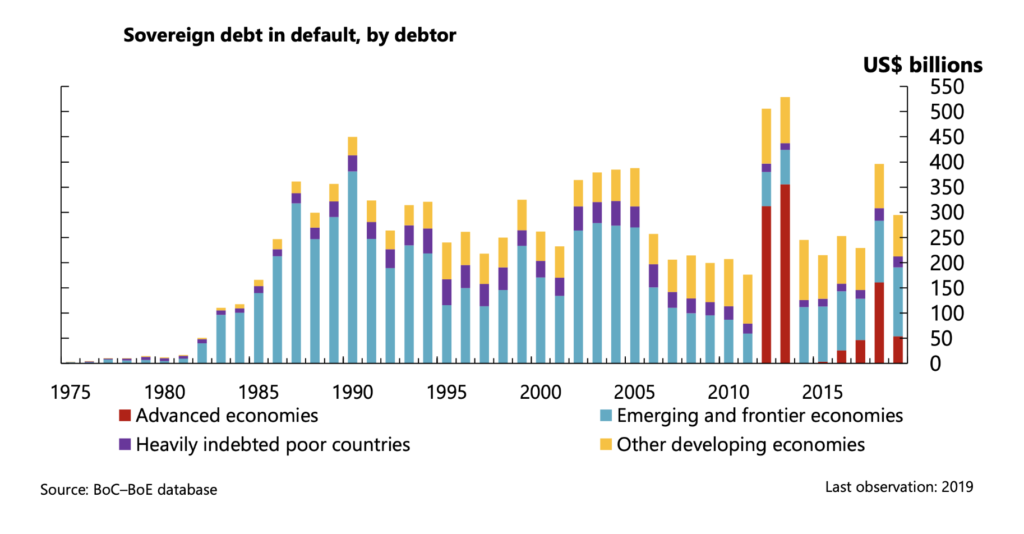

And here are all the billions of dollars of sovereign default measured from the mid 1970’s up to 2019. This doesn’t include the recent defaults of Russia and Sri Lanka.

The bottom line is, there’s no such thing as ‘risk free’:

WEF

📜 History of defaults

For those of us who live in developed countries and are not old enough to remember the global defaults of the Great Depression, the idea of sovereign debt crises may seem, well, a bit foreign.

The reality is, however, sovereigns defaults happen far more often than we may realize.

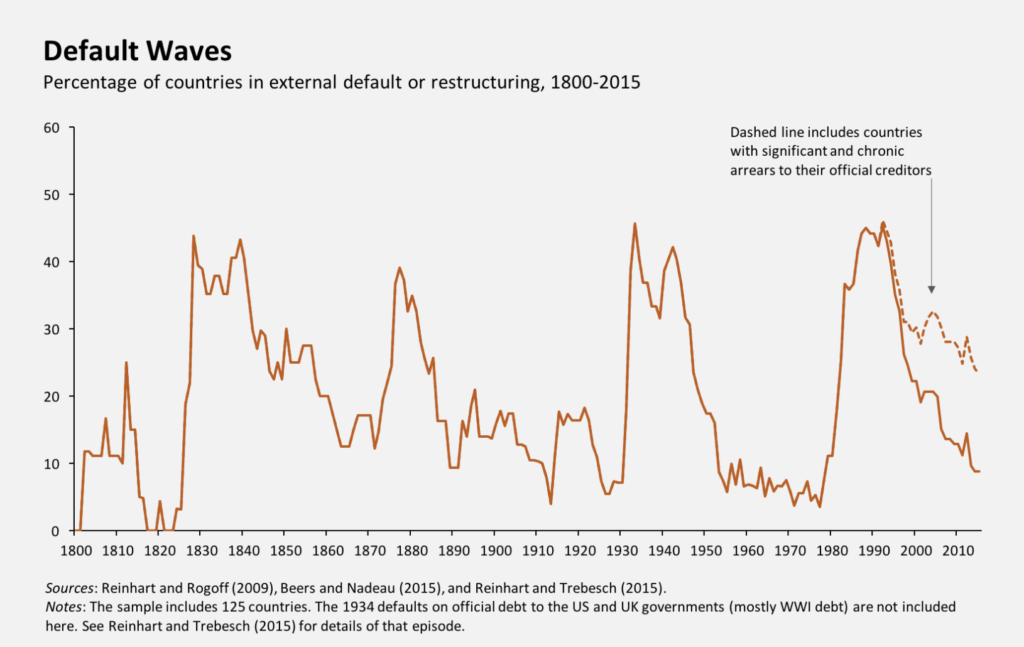

According to the IMF, there have been four main default peaks in the last 200 years: the 1830s, the 1880s, the 1930-40s, and the 1980s, where more than half of emerging market countries were in default in each period.

Additionally, the Great Depression wave of defaults in the 1930-40s was global, and the 1980s defaults included African and Asian developing countries.

WEF

An important thing to note here, advanced countries default far less frequently, and in 2012, Greece became the first advanced country to have a full debt restructuring since the 1960s.

So, let’s walk through what actually happens during a default.

🤨 What happens in a default?

As we learned above, countries facing liquidity issues and the possibility of inability to pay coupons on their debt can either wait until they actually default or they can enter discussions with the creditors (owners of their debt) before it happens.

These pre-emptive restructurings are often quicker, with negotiation time averaging 12 months, versus post-default restructurings which average ~60 months.

Either way, though, the negotiations ultimately lead to what is called a debt restructuring agreement. This restructuring settles on a new payment schedule that can include lower principal, lower interest payments, and/or longer maturities.

Any and all of these mean less money to the creditors.

The haircut.

The haircut is basically the percentage difference between the new debt value and the value of the pre-restructuring debt.

To calculate the haircut, investors will compare the present value of the new debt with the face value of the old debt:

Haircut = 1 – Present Value of New Debt / FV of Old Debt

Example:

Let’s say a Greek bond’s original face value was $1,000 and the restructured Greek bond became worth $250 in present value.

Haircut = 1 – 250/1000 = 75%

In other words, investors took a 75% haircut on Greek debt. By the way, this is the actual estimate put out by many banks, as the haircut range was between 73% and 78% in most instances for Greek bondholders.

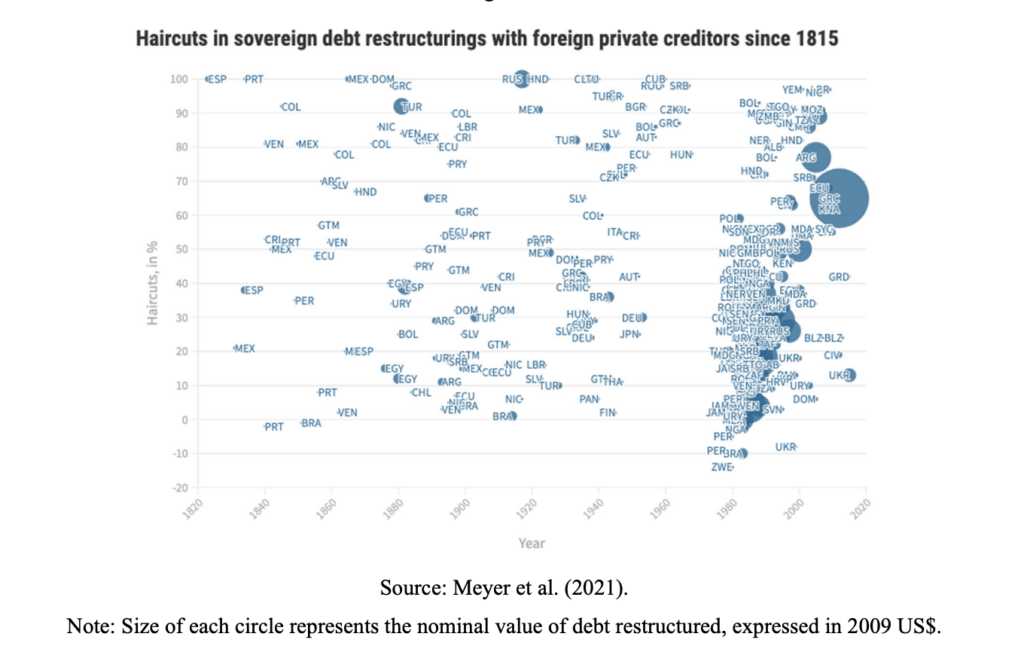

Looking a the chart below, you can see the calculated haircuts of sovereign defaults since 1815. The higher up on the chart, the larger the haircut (less the creditors were ultimately paid back) and the bigger the circle, the larger the sovereign default.

IMF

After a country goes through a default, it will likely be negatively impacted by increased borrowing costs due to perceived increased risk. Or worse, the country may suffer from capital market exclusion altogether, especially if the restructuring occurred post-default.

This means the capital markets exclude them from being able to issue or trade their debt internationally. Obviously a major negative impact to a country in the need of borrowing, and something to avoid at all costs for any country.

😇 Who’s most in danger to be next?

As you know, and as @BryanBSolstin points out in his Tweet above, we’ve had two developing or emerging market countries, Russia and Sri Lanka, default already this year, and there’s an increasing likelihood we see more in the coming months.

But what about developed countries? Are any in serious danger of default in the near future?

You may have heard me and numerous others talk about Europe recently, and the plain fact is that countries in the southern region of Europe, namely Italy, Greece, Portugal, and Spain, have weakening balance sheets and are facing an increasing danger of default.

Reasons for this include poor balance sheet management from their central banks with over indebtedness, increasing interest rates in the region due to inflation, heightened recession risks from super-inflated energy costs, as well as other factors.

For the moment, however, the European Central Bank (ECB) has instituted a new monetary policy instrument called the anti-fragmentation tool in order to prevent the breakdown and possible collapse of certain debt markets.

Namely Italy and Greece.

Basically, the ECB is buying Italian and Greek debt in certain maturities and at specific yields in order to provide liquidity and keep borrowing rates in those regions low. At some point, however, other more responsible countries in the ECB will balk at the continued subsidizing of these struggling economies and refuse to continue to support them.

Germany will someday say, no more.

And soon thereafter, you will see two, three, maybe four sovereign’s default on their debt.

When that happens, the EU will effectively break apart, there will be contagion on the debt of these western countries that spreads to others, and we will most likely see other non-European developed countries default on their debt, too.

Japan? Canada? The United States?

Nobody knows for certain, but as history has shown us and the math behind sovereign debt and revenue levels all but ensure, they eventually will.

That’s it. I hope you feel a little bit smarter knowing about sovereign defaults and what actually happens when they do.

Before leaving, feel free to respond to this newsletter with questions or future topics of interest. And if you want daily financial insights and commentary, you can always find me on Twitter!

✌️Talk soon,

James

Great article. Question though. I was under the impression that Russia “defaulted” because they literally had their US treasuries frozen by the US. How could they pay if they were prevented from paying? Honest question.

If I am wrong, then apologies.

Thanks for this article. It helps me understand how this happens. When a country defaults what happens at the level of individual citizen. Recently I heard that people in Lebanon cannot access their savings accounts and are having trouble making it from day to day.