*This article was originally written for and posted on Citadel21. You can find the article here.

An Important Choice

A couple of years ago, I was faced with a choice: Buy the farm that has been in my family for four generations, or let it be sold outside of my family. Which meant it would likely never be available for purchase again in my lifetime. Although I was still a student at the time, and not expecting to have to make that choice so soon, my intuition told me that this was something I needed to do.

Later that summer I went to one of the local money-printing offices and asked for some freshly minted fiat to help me realize my new dream. Under my arm I carried an excel sheet detailing the finances of my planned enterprises. It did the trick, and I was awarded a ticket on the ship of Cantillon. In other words, I got a loan and bought the farm.

Prior to this I had lived three years in the city of Oslo, including two lockdowns. It made the choice a lot easier. I was not meant to live in the city. In fact, it made me pretty sure none of us are. This unexpectedly fast pivot back to my roots led me on a search to figure out how I would carry the torch onwards. Thus, I ventured into another rabbit hole: Regenerative agriculture.

What is Regenerative Agriculture?

In short, regenerative agriculture is about fixing the faults of the past and getting back to farming on the premises of nature. To close the gap that we built between ourselves and the sustainable level of prosperity our earth can provide. Much like Bitcoin is doing in the monetary realm.

Since World War 2, most of the world’s farmland has been severely degraded through unnatural and unsustainable farming practices. A core aim of regenerative agriculture is therefore to actively regenerate the soil, while producing food in the same process. The end goal is to maximize the vitality of the ecosystem through natural processes, while still being able to fulfill human needs efficiently. By doing this we can heal the soil, our communities, and our bodies and minds at the same time.

One core similarity between regenerative agriculture and Bitcoin is that both are grassroots movements. Both have risen through the ashes of inevitably failed centralization in their domains. Both utilize social media, podcasting, public events, and super-secret underground group chats, to spread the message to the ones willing to listen.

The central banking cartel and the industrial agricultural complex have long thought that they can micromanage the economy and ecology, without unintended consequences. Or that these unintended consequences can easily be fixed by adding `just one more layer´. That the complexity of these systems must be tamed and controlled. That without their expertise, the uneducated masses would descend into the abyss.

On the other side, regenerative agriculture and Bitcoin embraces this complexity by letting nature express itself unconstrained. To let each individual – like a bison, tree or cricket – act in its own best self-interest, to the greatest benefit of all.

A Soil Problem

With the raging inflation, bank collapses and regional social unrest we are seeing around the world today, it is obvious to many that the centralized micromanaging of the money is not working very well. What is less evident to most, is that we are seeing similar symptoms of collapse in the agricultural realm.

Most of the food we are consuming globally today, is produced in a way that degrades and erodes the soil it is produced from. It is estimated that 24 billion tonnes of fertile soil is lost to erosion every year. The soil that is left, continues to decrease in carbon levels, water holding capacity and microbial life. In short, this means we cannot expect to continue producing food with today’s methods indefinitely.

It was not always like this. In fact, the practices of today are fairly new in a historical context. And like with the origin of our rotten monetary system, we can find the answer in the history books.

Gunpowder

In the 1800s, while the industrial revolution transformed the world in various ways, a battle to become the ruler of the ever-smaller world was being fought out between the most advanced nations. As coal, steel, the steam engine and better weapons intensified the battle for each passing decade, one limiting factor in particular became evident: Gunpowder. Or more specifically the main ingredient in gunpowder, potassium nitrate.

As the demand for potassium nitrate increased, more efficient ways of sourcing it was needed. In 1804 Alexander von Humboldt brought good news to the shores of Europe: Guano. Caves, and even islands, full of the manure from birds and bats rich in nitrogen, phosphate and potassium. As the concentration of the needed elements was way higher in guano than in regular animal manure, the production of gunpowder increased dramatically. Thus, the valuable resource increased the military`s capacity for violence until around 1890, when the guano was mostly gone. But the countries, like heroin addicts, could not stop shooting. They needed more gunpowder and found ways of getting it.

In 1913, the same year as the Federal Reserve was founded, the Haber-Bosch method was first put to industrial scale production in Germany. The method converts atmospheric nitrogen to ammonium, which is then converted to nitrate. This gave Germany a head-start at mass producing the modern war machine`s biggest bottle neck and was a major contributing factor to the 30 dark years of world history that followed.

Weaponized Agriculture

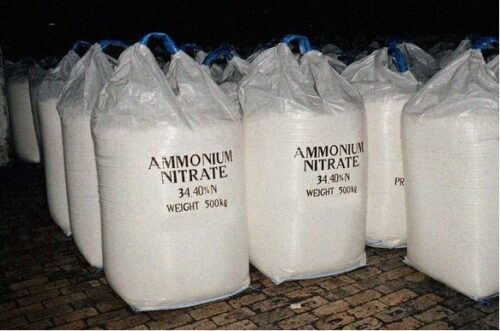

But what does gunpowder and war have to do with farming? Well, as WW2 came to an end in 1945 most people were relieved. Except the ammonium nitrate producers. They needed new customers. In his recent appearance on the Joe Rogan Experience, Will Harris of White Oak Pastures, one of the largest regenerative farms in the world, tells the story of how it unfolded on their farm.

In 1946 a salesman came to their town Bluffton in Georgia, with 400 pounds of ammonium nitrate fertilizer. The same thing that was previously used in munition production. Then he gave the local farmers a small amount each and told them to spread it on a small patch of land, water it, and come back in three days. The grass was already an order of magnitude taller and greener than the surrounding area, and the rest is history. Since then, the use of ammonium nitrate and other synthetic fertilizer compounds has skyrocketed on a global scale. As a result, food has increasingly become mass produced commodities that are cheap and abundant. While this has allowed us to feed a growing global population, it has not come without negative side effects.

A Vicious Cycle

There is little doubt that much of the food we consume today has a detrimental effect on our health. Although this alone is an important reason why we should question today’s farming practices, the degrading impact it has had on the soil is arguably worse. Or rather the dirt it is produced in.

Because as we started using chemical fertilizer to increase yields, we went from producing food from soil, to producing food in dirt, and in the same process lost most of the actual soil. There are many factors contributing to the loss of topsoil, including repeated tilling of the soil and applying chemical fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, and fungicides. Although tilling is not a modern invention, the negative impact it has on soil cannot be understated.

Every time the top 20 cm of the field is turned around, and bare soil comes in contact with air, carbon from the ground oxidizes and flies off as CO2. Thus, we lose plant food, soil structure and water holding capacity – all essential factors for living soil. The fact that nature always covers up bare soil as quickly as it can, should give us a clue that turning it around and leaving it bare for months is not a good idea.

When we add chemical fertilizers to the mix, the negative effects of today’s practices become even more obvious. As chemical fertilizers are water soluble, it makes it easy for the plants to absorb the nutrients in it. Although this may sound great, it has some serious negative side effects. The short explanation is that it disables the plants’ ability to express their natural behavior of “eating” the combination of nutrients and micronutrients they need. This weakens the plants´ natural immune system, making them vulnerable for insects and disease.

“Luckily”, the chemical fertilizer companies have a solution, and a sales budget, for these problems. All these solutions end with “-cides”, which comes from latin and means “killer”. We then use these cides to kill the organisms that the plant’s immune system would naturally protect it from.

To conclude, today’s farming practices are characterized by releasing the carbon into the air, impairing the soils´ water holding capacity, adding a synthetic mix of fertilizers, and killing the organisms that stand between us and maximized production. In this process we decrease soil life, destabilize ecosystems, and end up with enormous amounts of cheap but nutrient diminished food.

The Road Forward

So, what is the solution to all these problems? In my opinion there are a few things that need to happen for the situation to improve. First of all, I don’t know a single farming colleague that does not want the best for his land, animals, family and community. Yet, many are working ever longer hours, despite their family’s wishes to spend more time together. Running ever larger operations, where the only thing falling quicker than the ecological diversity, is the profit of the operation.

The way I see it, these are the two main reasons for this situation:

- Time theft through inflation

- Lack of ownership to the land, operation, and end product

The solution to number one is the most obvious. It is not only in the agricultural industry that our time seems to have become scarcer over the years. Time theft, whether it is 2%, 10% or 50% annually, needs to end. The only solution to this is Bitcoin.

The solution to number two is more complicated. The endless lists of rules, regulations, reporting and inspections that exist in agriculture today, is probably only surpassed by that of starting a bank. These attempts at micromanaging for optimization and steer farmers towards `desired´ productions, has slowly changed what it means to be a farmer.

Rather than figuring out how we can create the most value with our resources, we spend time making sure we stay compliant with regulations and maximize our subsidies. Since the incentives have pointed towards increasing the yields for decades, few of us ever meet the people that consume our food. And many of our consumers have no idea how the food is even produced. There are just numbers coming in and numbers going out. Farming has become a transaction.

Taking it All Back

So how can we take back our food system? I think we need to do exactly what Bitcoin has done to money. Go back to the basics. To farm on the principles nature has set out for us, like Bitcoin functions on mathematics and code. To stop trusting a central authority to know better than ourselves how to utilize the resources we have at hand.

A farmer should trust a chemical fertilizer company as much as a bitcoiner trusts a bank. We need to build a bridge between end consumers willing to pay the price for hard food, and farmers willing to be accountable for the product they offer. Shake your rancher’s hand.

And of course, we should settle the trade in hard money as well. To starve the beast that put us in the situation to begin with. Then we can take back the food and the money at the same time. And I don’t think we can truly take back one without the other.

Fix the food, fix the money. Fix the money, fix the world.